When I began writing The Feedsack Dress almost 50 years ago, I asked my mother and two sisters to talk about their memories of 1949. I’d chosen that year for the novel because my recollections and my research identified it as a time of transition for the country, our rural Missouri community, and our family.

Our discussion evoked many forgotten details and produced a major plot point.

We gathered around the kitchen table at my parents’ farm on a hot summer day. To my surprise, each of us remembered not only different movies and music but also different versions of events, including family reunions and what happened when I broke my arm. (I tested the knot in a rope I’d tied around a tree limb by sliding down it. The knot failed the test.) The discrepancies convinced me of the unreliability of eyewitness accounts, a factor I consider in writing both nonfiction and fiction.

Judy, four years younger than I, remembered the least, but even she recalled the drudgery of pumping water for the milk cows and the excitement when REA extended the electric lines past our place. Overnight my parents could milk triple the number of cows, my mother didn’t have to bear the heat of a wood cooking stove, and we could listen to Kirksville’s new radio station without fear of running down the battery and read under strong lights rather than dim kerosene lamps. Electricity improved our daily lives and increased our income.

Donna and I spent many hours on 4-H sewing projects. Our mother taught us to sew on a treadle machine, using patterned feedsacks that had contained chicken feed to make tea towels, potholders, pillow slips, and, as our skills grew, clothing—skirts, blouses, shorts, and dresses. An electric sewing machine made the work easier. New synthetic fabrics didn’t, at least for a couple years.

Unlike me, Donna loved to sew, partly because it gave her a chance to expand her limited wardrobe in an age of hand-me-downs. Five years older than I, she’d been born in the Depression, walked alone a mile and a half to the one-room school (New Hope) that my father and his mother had attended and at which my mother had taught, and become a teenager as my parents put aside every possible penny to pay off the farm they bought at the end of World War II. My big sister became a skilled seamstress. For decades she took pleasure in making clothes to wear to college and then to work as a bookkeeper. She also made clothes for others, including her kids and me.

I took special note of Donna’s difficulties in moving from a class of three in a grade school with about 15 pupils to classes of 30 in a junior high with about 500 students. She was tiny and timid, preferring to be unseen and silent. Our grade school’s limited resources and mediocre teaching hadn’t prepared her well for the tough competition. (Judy and I had an excellent teacher and went to town better prepared.) Determined to hold her own, Donna studied hard and earned membership in the National Honor Society. One test day when snow blocked the roads, she persuaded my father to take her the five miles to high school on the tractor.

A key plot point for The Feedsack Dress came to me when Donna vividly recalled ninth graders passing around slam books, often the little autograph books then popular, with mean comments about fellow students. My protagonist has to deal with those slams as she forms friendships and makes enemies.

I recalled the four of us talking about 1949 recently because my big sister, Donna Lee Mulford Helton, died February 5, 2021. Now no one shares those memories.

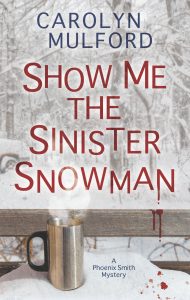

—Carolyn Mulford