When The Feedsack Dress came out in 2007, I started a blog on Typepad that focused on life during the late 1940s and early 1950s. I stopped posting there in 2012, but you can still link to The Feedsack Kids. I’m posting some new blogs and my favorite old ones here.

Category Archives: The Feedsack Dress

4-H and Sewing in the 1940s

4-H came to my rural community about two years after World War II ended. We had no other youth organizations available, so 4-H, led by two wonderful (female and male) county Extension agents, made a huge impact on us children—and our parents.

As I recall, the whole community met at New Hope School (grades one through eight) to hear the agents describe the program and recruit adult volunteers to lead projects teaching practical skills ranging from sewing to raising calves. Then all the dozen or so kids nine or older signed up, elected officers (an unfamiliar task), and took the pamphlets home to choose their projects. Being only eight, I envied my older sister and listened closely to discussions there and at home.

My mother studied the materials thoroughly, for volunteer leaders had to master and teach the standards 4-H set for each project. A former teacher, she had been making our clothing for years, but she felt that she needed the guidance the pamphlets and the agent provided. I later realized that 4-H educated parents as well as children.

By my ninth birthday, I had memorized the 4-H pledge, learned basic parliamentary procedure (a boon forever), and reconciled myself to tackling cooking and sewing projects rather raising a calf. I didn’t mind making biscuits and cakes, but I preferred to leave the sewing to my big sister, who loved it. The first year was basic: threading and operating our treadle sewing machine, using paper patterns to cut cloth, sewing straight seams in such items as tea towels and pillow slips. To my dismay, my mother made me redo everything until it was perfect.

The second year the project got harder. I came to hate sewing. I liked going to the feedstore and choosing the sacks for my practice rounds of shorts, blouses, and skirts, but the summer heat turned cutting and fitting and putting in and taking out imperfect seams into torture. I suffered through five summers of sewing projects. I earned blue ribbons at the fair for blouses with button holes and dresses with zippers and for judging others’ work. The successes didn’t compensate for the time robbed from reading and playing outdoors.

4-H taught me many other useful skills, including how to give a demonstration, how to speak in public, how to work with a group, and how to do well a job I didn’t like.

And I’ve never forgotten the pledge: I pledge my Head to clearer thinking, my Heart to greater loyalty, my Hands to larger service, and my Health to better living for my club, my community, and my country.

—Carolyn Mulford

Where to Find My Books

While only one of my books, Show Me the Sinister Snowman, continues to be published in print and electronic editions, several of my novels are available from online sellers. Most of the copies are used, but columbiabooksonline.com, my supportive local bookstore, has a small stock of new Show Me hardbacks and paperbacks.

I also have a few copies of all my novels except The Feedsack Dress, my historical children’s book, and Show Me the Murder, the first in my mystery series featuring a former spy returning home and solving crimes with old friends. Fortunately e-editions still exist. Barnes and Noble carries The Feedsack Dress ($2.99), and Amazon offers Show Me theMurder ($3.99).

A search of used-book sites, such as abebooks.com, may turn up copies of all my books—even the nonfiction ones that are so old they must have come from estate sales.

You may still find my novels at your local library or ask it to borrow these for you through the interlibrary loan program.

I’ve no new books to announce, so I hope readers will continue to enjoy the old ones.

—Carolyn Mulford

My One-Room School

In the 1940s, my sisters and I sometimes wore feedsack dresses, blouses, and skirts to the one-room school a half mile from our farm. Our family had a history there. My grandmother’s family had donated the land for the school, my father had received his eight years of education there, and my mother had met him while teaching there and spending her summers taking undergraduate courses.

On a typical day, we rushed to school to play a few minutes before the teacher rang the handbell at 8:55 for our 9 o’clock start. In mild weather, the dozen or so pupils in grades one through eight said the Pledge of Allegiance outside facing the flag.

We seated ourselves at old wood-and-metal double desks with the youngest children in the front rows. Each desktop had a hole for an inkwell, but the bottles of ink for our little-used fountain pens usually went onto the open shelf underneath with our few books, Big Chief tablets, pencils, and crayons.

The teacher had a big wood desk up front. Blackboards filled the back wall, and rolled-up maps of the world and the United States could be pulled down when needed. Big casement windows lined the north and south sides of the room. The left front corner hosted the World Book Encyclopedia and the pencil sharpener. An upright piano occupied the right front corner. In the back were a coal stove, coat hooks, and two metal cabinets containing textbooks and recreational reading.

Classes began with the first graders going to the teacher’s desk to read aloud from Dick and Jane books. The rest of us studied for our lessons to come, each class taking its turn with the teacher until the first recess. In that 15 minutes we raced to the outhouses (one for boys, one for girls) at the edge of the schoolyard, pumped water for a drink from the well beside the school, and enjoyed minutes on the swings, see-saw, or slide.

Then we returned inside for arithmetic, usually checking problems we’d completed on paper and working others on the blackboard. To cut down on the number of classes, the teacher taught fifth grade and seventh grade one year and sixth grade and eighth grade the next—except for arithmetic. That had to be studied in sequence.

Other major subjects were spelling, history, science, and geography. When a school program, such as a pie supper, was coming up, we adde music—mostly singing or playing little flutes called Tonettes or such rhythm band instruments as sticks, blocks of wood covered in sandpaper, bells, a triangle, and a drum.

Precisely at noon we ate lunch, typically soup from a thermos or a bologna or peanut butter sandwich, a piece of fruit, and cookies. In good weather we played outdoor games that kids of all ages could play, including group tag, May I, andy (ante) over, and baseball. In bad weather we often played jacks (using up to 40) or pick-up sticks on the teacher’s desk.

At 1 p.m., we took our seats, and the teacher read a chapter from a novel. In first grade I was spellbound by The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. Mark Twain remains one of my favorite writers.

We all looked forward to Friday afternoons. We cleaned the school and then chose teams for contests—finding places on the maps, working arithmetic problems on the blackboard, and holding a railroad spelling bee. In the last, a team captain spells railroad, and the other captain spells a word beginning with the final letter (d). The team members take turns spelling words beginning with the last letter of the last word spelled. Little kids could compete with the older ones by spelling simple words, especially ones that ended in x. Failure to think of a word or to spell it correctly eliminated the speller. The team with the last speller standing won.

The day ended at 4 p.m. No one stuck around to play. We all had chores—gathering eggs, pumping water, shelling corn, feeding animals—waiting for us at home.

The one-room schools in my county closed in the early 1950s right after my younger sister graduated from the eighth grade. With the school population dwindling and resources limited, the schools were no longer economically viable. From then on, the country kids rode school buses to schools in town.

Some schoolhouses survived a few years as community centers, private homes, or storage space for hay. Today you’re no more likely to see a one-room school than you are a feedsack dress.

—Carolyn Mulford

Messing with Easter Eggs

Recently a TV “news” program showed a new scientific advance—a mess-free way to color Easter eggs.

The reporter—a parent—enthused over the convenience as a saleswoman placed a boiled egg in a holder, poured a liquid color into a mini tank behind it, and automated tiny brushes that made uniform blue lines on the rotating egg. She explained that the gadget offered other colors and patterns.

Neat but boring, I thought. Do kids today really enjoy programmed designs more than individual creativity? Back in the feedsack days, my sisters and I relished blending colors and making each egg distinctive. Have attitudes changed that much?

Coloring eggs highlighted our Easter celebrations. We chose some 15 to 20 eggs from our daily gathering to clean and boil, bought a rainbow of colors (in powdered packets, if I remember correctly) to supplement whatever food colors were on hand, and prepared our colors in old cups arranged on the kitchen table. We dipped the eggs into the cups with fingers, spoons, or tongs, often using several dips to vary the colors and designs. Blue, pink, yellow, and green dominated.

The whole process was very, very messy, a rare indulgence in my mother’s kitchen.

About the only eggs emerging with only one color were those on which we drew or wrote our names with a (wax?) marker that the coloring didn’t penetrate.

Early Easter morning my mother played bunny, hiding the eggs in the yard for us to hunt and place in our cherished dimestore baskets. As we got older and the economy improved, she added small chocolate eggs covered in bright paper. If wet weather prevented an outdoor hunt, she hid the eggs in the house. Either way, we competed to find the most edible treasures.

We all loved to eat the chocolate eggs. Only I relished the boiled ones, so those lasted a couple of days. I took mine to school for lunch.

The last Easter egg hunt that I remember on the farm occurred when my nieces and nephews were young. I did the hiding. My sisters enjoyed the hunting more than their kids did.

This year I’ve colored no eggs and won’t hide or hunt any, but I’ll never forget how much we enjoyed messing with Easter eggs.

—Carolyn Mulford

Why I Wrote The Feedback Dress

Over more than 30 years, I wrote and rewrote The Feedsack Dress, my first published novel. For the record, here are my recollections of why I began writing it and why I persisted in finishing it and finding editors smart enough to buy it.

I grew up on a small farm near Kirksville, Missouri, in the 1940s and 1950s. With cows to milk morning and evening, we stuck close to home, but on Sunday afternoons my father sometimes drove us around on the gravel roads to see how the crops and livestock were faring on other farms.

My world expanded mightily in 1962 when I joined the Peace Corps. I served as an English teacher for two years in Ethiopia and then traveled (on $5 a day, for the most part) through the Middle East and Europe on a slow trip back to the States.

After working on a magazine in Washington, D.C., for two years, I thirsted for foreign places. An editorial job at a U.N. organization headquartered in Vienna, Austria, enabled me to live (and travel) for three years in Europe. I spent a six months going home through the Middle East, Asia, and Australia.

I returned to the family farm to regroup in 1971. When my parents and I followed country roads to look at familiar places, I saw that my childhood world had changed considerably. Most of the one-room schools and churches had disappeared or been repurposed, leaving no place for neighbors to gather. Several once well-kept farmhouses had broken windows and weedy yards. Chickens no longer ran free near occupied houses. Teams of horses, even retirees, had given way to large tractors and unfamiliar equipment.

The traditional small farm where the family raised much of its food and named most of its animals was being consumed by agricultural enterprises, an accelerating trend that depressed my parents.

Recalling the swift changes following World War II, I reflected that my generation was the last to grow up on a small diversified farm. The transformation from labor-intensive to mechanized farming and from a rural to an urban society had both benefited and disrupted lives.

I kept coming back to these thoughts for a couple of years, reading social histories to supplement my memories and knowledge of the postwar period. Personally and nationally, we’d experienced a great transition, and I wanted to write about it. But in what form? I didn’t have the academic credentials to write a social history or the inclination to write a memoir, and postwar rural northeast Missouri wasn’t a marketable topic for magazine articles.

I’d always wanted to write fiction, and a children’s novel seemed the right choice for the story that my memories and research were germinating. Historical events and economic developments that affected my community and the nation led me to set the story in 1949. For example, the Rural Electrification Act’s lines finally reached us (increasing the number of cows we could milk, decreasing time spent on housework, and enabling us to read and study at night). We bought our first brand-new car (a symbol of growing prosperity).

4-H had come to our community, and mothers joined us in learning to make clothes from such new synthetics as rayon and acetate as well as from cotton feedsacks, a staple for clothing and tea towels during the Depression and the war.

The colorful patterned sacks became my symbol of individual and societal transition—and of being different. By now I’d observed that being unlike the majority—in economic class, skin color, language, religion, whatever—posed a problem wherever you are in the world. Dealing with being outside the norm challenges anyone at any age, but it’s particularly painful for teenagers discovering their own identity. So I forced my heroine to endure being the only girl wearing a feedsack dress as she goes from a one-room country school to ninth grade in town.

The book is set when my older sister went through that culture shock, and the plot is not autobiographical. That doesn’t mean elements aren’t real. The mean girl’s nasty remark about the riffraff on the square on Saturday nights actually came from a favorite teacher, who apologized profusely when I pointed out my family was part of that crowd. I certainly grew frustrated with facing new games in gym class just as I’d learned to play the last one.

I drew on memories in describing mule races and killing chickens. Most events came from my imagination. I don’t remember whether my class elected officers. That plot element derived from the Nixon campaign’s dirty tricks.

Just as Gail, the protagonist, is not me, the other characters are not relatives or classmates. At Class of 1957 reunions, they’ve guessed whom my characters were based on, often naming teachers I never had. I created most by adapting bits of people I’d known during and after high school.

This was my first novel, a major learning experience. I began writing with a setting, a few characters, and little idea of what to do with either. The characters’ personalities and relationships emerged quickly, but the plot had little direction until I realized I needed a major conflict. The first draft that I submitted to agents ended right after the class election. An agent told me I couldn’t end the book on a down note, and I expanded the plot.

The revision still didn’t appeal to New York editors. I put the manuscript aside for years at a time but always came back to it. Each time I reread it, I liked it too much to give up on revising it and finding a publisher.

Thirty years from the time I started writing, I was working with a critique group of mystery writers. Although they were Eastern city slickers, they agreed to give me feedback on The Feedsack Dress. Their ignorance of farming and the mid-century Midwest guided me in clarifying terms and describing things common to me but not to later generations and urbanites.

In a national writers’ newsletter, I read that Cave Hollow Press, a small publisher in Missouri, welcomed submissions set there. The editors bought my manuscript, did a light edit, and published it in July 2007. At the end of 2023, the publisher had six copies left in stock.

In 2009, the Missouri Center for the Book chose The Feedsack Dress as the state’s Great Read at the National Book Festival on the Mall in Washington, D.C. The warm reception that readers gave The Feedsack Dress encouraged me to continue my transition from nonfiction to fiction.

Few print copies of this novel remain available, but you can buy the e-book at https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/the-feedsack-dress-carolyn-mulford/1103622141?ean=2940012128485.

Why we needed Title IX before 1972

The fiftieth anniversary of Title IX, a landmark law requiring gender equality in schools receiving federal funds, reminded me of how little opportunity to play sports most females of my generation had. (Title IX changed much more than sports, but that’s another story.)

In my one-room school with roughly a dozen students in grades one through eight, we had no organized physical education program for girls or boys. We played together at recess and noon, mostly baseball or games involving some form of tag. Our entire sporting equipment consisted of two bats, a softball, a baseball, and a volleyball (used for playing handy-over, with half the school on one side of the coal shed and half on the other).

In ninth grade, as I wrote in The Feedsack Dress, the most familiar sport to country kids—and the least played in girls’ P.E. class—was softball. By the time I learned the basic skills of an exotic game like deck tennis (played much like volleyball but with a hard rubber ring), a new game popped up. I added little to my homeroom’s intramural teams.

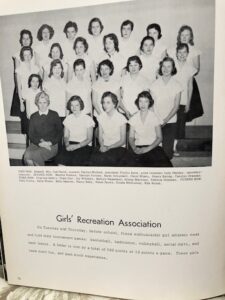

Neither my senior high school nor college in Kirksville, Missouri, fielded girls’ teams that competed with other schools. Neither had a swimming pool, and the high school had no playing field or tennis courts for girls. High school P.E. classes met in the basement gym. There we did boring calisthenics and played deck tennis, aerial darts, badminton, volleyball, and basketball. I was surprised to learn I had lettered my senior year (rare for a girl). I did it by recruiting the school’s best players for my intramural teams. If my memory is accurate, we won all the tournaments. The only mention of girls’ sports in the high school yearbook was the page above, which shows the members of the Girls’ Recreation Association (I’m second from left on the front row).

The college’s program offered little more than the high school did, though I did learn to play table tennis and jump on a trampoline. My athletic high point: The women’s P.E. Department (two women) let me substitute a softball elective for a required calisthenics course. As a grad student at the University of Missouri, I saw no opportunity to participate in any sports. One woman among several men in the renowned journalism school aspired to be a sports writer.

Finally, during Peace Corps training at Georgetown University, I received introductions to swimming, soccer, and cross-country running. My physical education consisted of appetizers but no main course.

The real national awakening to the potential of women’s sports took place in September 1973, more than a year after Title IX, when Billie Jean King took down Bobby Riggs in the Battle of the Sexes. She changed not just tennis but the recognition of women as athletes. She has continued to push for equal pay and power on the court and off ever since.

Even with the much greater (though not equal) opportunities today, I wouldn’t have become a great—even a good—athlete, but several of my classmates could have. And school would all have been more fun.

Equal opportunity, wherever you find it, makes life less frustrating and more rewarding.

—Carolyn Mulford

Memories Sparked The Feedsack Dress

When I began writing The Feedsack Dress almost 50 years ago, I asked my mother and two sisters to talk about their memories of 1949. I’d chosen that year for the novel because my recollections and my research identified it as a time of transition for the country, our rural Missouri community, and our family.

Our discussion evoked many forgotten details and produced a major plot point.

We gathered around the kitchen table at my parents’ farm on a hot summer day. To my surprise, each of us remembered not only different movies and music but also different versions of events, including family reunions and what happened when I broke my arm. (I tested the knot in a rope I’d tied around a tree limb by sliding down it. The knot failed the test.) The discrepancies convinced me of the unreliability of eyewitness accounts, a factor I consider in writing both nonfiction and fiction.

Judy, four years younger than I, remembered the least, but even she recalled the drudgery of pumping water for the milk cows and the excitement when REA extended the electric lines past our place. Overnight my parents could milk triple the number of cows, my mother didn’t have to bear the heat of a wood cooking stove, and we could listen to Kirksville’s new radio station without fear of running down the battery and read under strong lights rather than dim kerosene lamps. Electricity improved our daily lives and increased our income.

Donna and I spent many hours on 4-H sewing projects. Our mother taught us to sew on a treadle machine, using patterned feedsacks that had contained chicken feed to make tea towels, potholders, pillow slips, and, as our skills grew, clothing—skirts, blouses, shorts, and dresses. An electric sewing machine made the work easier. New synthetic fabrics didn’t, at least for a couple years.

Unlike me, Donna loved to sew, partly because it gave her a chance to expand her limited wardrobe in an age of hand-me-downs. Five years older than I, she’d been born in the Depression, walked alone a mile and a half to the one-room school (New Hope) that my father and his mother had attended and at which my mother had taught, and become a teenager as my parents put aside every possible penny to pay off the farm they bought at the end of World War II. My big sister became a skilled seamstress. For decades she took pleasure in making clothes to wear to college and then to work as a bookkeeper. She also made clothes for others, including her kids and me.

I took special note of Donna’s difficulties in moving from a class of three in a grade school with about 15 pupils to classes of 30 in a junior high with about 500 students. She was tiny and timid, preferring to be unseen and silent. Our grade school’s limited resources and mediocre teaching hadn’t prepared her well for the tough competition. (Judy and I had an excellent teacher and went to town better prepared.) Determined to hold her own, Donna studied hard and earned membership in the National Honor Society. One test day when snow blocked the roads, she persuaded my father to take her the five miles to high school on the tractor.

A key plot point for The Feedsack Dress came to me when Donna vividly recalled ninth graders passing around slam books, often the little autograph books then popular, with mean comments about fellow students. My protagonist has to deal with those slams as she forms friendships and makes enemies.

I recalled the four of us talking about 1949 recently because my big sister, Donna Lee Mulford Helton, died February 5, 2021. Now no one shares those memories.

—Carolyn Mulford

Summer Before Air Conditioning

Air conditioning keeps me comfortable during the current heat wave, but I remember how we tried to cool off when nothing but the movie theater was air conditioned.

July and August approximated hell when I was a kid. No day was so hot that we wouldn’t work in the fields and the garden. Only the persistent breeze made the heat and humidity bearable.

The steamy days heated the house, making it equally miserable. When we got electricity, fans helped a little. During the day the coolest place to be was in the shade of a big elm. (Sadly Dutch elm disease killed these majesic trees some 50 years ago.)

After we’d milked and watered the cows in the evening, we’d sit on the front porch to catch the breeze, or to create it by swinging in the swing suspended from the porch ceiling with chains. When the sun set and the lightning bugs came out, my sisters and I would leave the porch to catch bugs to put in a fruit jar. We’d also compete to see the first star (the one you wished on) and then the Big Dipper.

Most nights we’d sleep inside, often after sprinkling the sheets with water the way we did the clothes before ironing them. On particularly hot nights, my sisters and I would spread an old blanket on the grass and try to sleep there. I don’t think we ever lasted the whole night. Chiggers, mosquitoes, and dew drove us inside.

Despite the discomfort, those nights sleeping in the yard thrilled me. The star-stuffed sky offered a magical, memorable panorama.

Carolyn Mulford

Mixing Memories and Research

When I started writing The Feedsack Dress, my own memories of farm life and the ninth grade guided the plot, but I needed facts about life in 1949. I looked for them in the same places I would have if I were writing an article.

At the library I wore out my eyes scrolling through microfilm copies of the Kirksville Daily Express and two great photo magazines, Life and Look. These answered such questions as the styles of dresses or skirts and blouses a fashionable ninth grader wore to school and how much they cost. Few girls wore jeans or slacks to school back then.

Copies of fair catalogs told me what exhibits 4-Hers would enter in hopes of winning prize money. As a 4-Her in the 1940s and 1950s, I knew that only country kids belonged to 4-H then.

Books and local and national newspapers told me about historical events. By the time I did my final draft, I used the Internet to find such riches as President Truman’s speeches, the history of feedsack dresses, and lists of popular songs, radio shows (almost no one had television), movies, and books.

The most enjoyable part of the initial research was talking to my mother and others who remembered 1949 well. They linked important events in their lives to that year. They, and I, recalled how a chicken bounded around after a well-aimed hatchet removed its head and the awful stench when you dunk the chicken into a bucket of hot water to make it easier to pull out the feathers.

Some things you’d rather forget.