When The Feedsack Dress came out in 2007, I started a blog on Typepad that focused on life during the late 1940s and early 1950s. I stopped posting there in 2012, but you can still link to The Feedsack Kids. I’m posting some new blogs and my favorite old ones here.

Category Archives: News

Mid-Continent Earthquakes, Past and Future

About 2:30 a.m. December 16, 1811, an earthquake threw people in New Madrid, Missouri Territory, out of bed and crumbled brick houses and cabin chimneys, forced the Mississippi River to run backward and change course, disturbed sleep along most of the East Coast, and toppled dishes from shelves in the White House.

That marked the beginning of some of the most powerful, prolonged quakes the United States has experienced. These weren’t the first in the New Madrid Seismic Zone, which is centered near where Missouri, Arkansas, Tennessee, and Kentucky come together. Geologists and other scientists have found indications that powerful quakes—rating 7 or higher on the Richter scale—have occurred there periodically for roughly 4,500 years.

Scores of small quakes—many in the 1.5 to 2.5 range—still pester area residents each year.

Geologists expect more big ones to come, estimating a 10% chance that will be within the next 50 years. The area between St. Louis and Memphis is likely to be the hardest hit, but right now the spread and range of the next disastrous earthquakes can’t be predicted any more precisely than the time.

Scientific research on the past and the possible future of the seismic zone continues. The quakes are not just an academic interest. In 2011, an expert panel concluded the zone “is at significant risk for damaging earthquakes that must be accounted for in urban planning and development.”

My characters in Thunder Beneath My Feet had little information on what was happening elsewhere or what to expect as dozens of big quakes and aftershocks and hundreds of tremors hit New Madrid on an unpredictable schedule for weeks on end. Many people there, and elsewhere, thought the world was ending. For hundreds, it did.

I relished researching the unique historical events and creating characters representing the thriving, diverse (Spanish, French, American, Indigenous) community in the frontier riverport. For months, they faced daily terrors, and so will a much larger population when the next big ones hit.

Each fall preparedness groups in the area hold Great Shakeout Earthquake Drills. They recommend these three steps if you feel a quake begin.

- Drop onto your hands and knees so you won’t fall down and can crawl to any nearby shelter.

- Cover your head and neck with one arm and hand to protect you as you crawl under a table, desk, or anything else that will protect you from falling objects. If you have no shelter nearby, crawl to an interior wall, preferably a corner.

- Hold on to your shelter but be ready to move if it gives way.

Happy anniversary.

—Carolyn Mulford

Concert Jogs Memories of Vienna

Memories interrupted my enjoyment of the Vienna Philharmonic’s New Year’s concert broadcast last night on PBS.

Unlike my Show Me protagonist, a CIA covert operative embedded in Vienna, I lived there only three years, but we shared a love of the city’s music. I went to the opera, an orchestra concert, chamber music, an operetta, or some other musical performance once or twice a week. Tickets were cheap, particularly if you were willing to sit in the balcony directly above a chamber orchestra using the instruments in vogue when the music was composed centuries ago.

You could usually get a late ticket to stand at the back of the Musikverein’s high-ceiling rectangular grand hall, and people were there at last night’s event. I could spot where I stood to hear Leonard Bernstein as a guest conductor.

Every venue has excellent acoustics, and every audience knows the music and expresses approval or disappointment through applause. The Viennese love traditional favorites, including such Strauss compositions as Tales of the Vienna Woods. Even so, the 2022 performance included something I don’t remember hearing before, the musicians augmenting their instruments with singing and whistling at one point. The audience approved.

As usual, the favorite final encore, “The Radetsky March,” elicited an enthusiastic audience response. Everyone clapped without missing a beat.

The music lovers wore masks and the walls gleamed with gold (lacquer?) last night, but the orchestra’s performance and the audience’s appreciation have not changed.

—Carolyn Mulford

New Sinister Snowman Edition

Covid-19 stopped printers cold last spring. Consequently, the mass market paperback edition of Show Me the Sinister Snowman missed its slot in the printing queue. With the snow gone (until next winter, I hope), Harlequin Worldwide Mystery has just released the fifth book in the Show Me series.

This one finds Phoenix and friends trapped in an isolated mansion by a blizzard. Their housemates are aspiring political candidates and potential donors, one of whom intends to lessen their number before the roads clear.

Phoenix has come to the meeting with two goals: to support Annalynn’s electoral dreams and to rescue a young woman on the run. The former CIA operative’s dual objectives force her to guard against an unidentified murderer within the sprawling antebellum house and a vicious hunter in the deep snow outside it. The latter and Achilles, Phoenix’s clever Belgian Malinois, are the only ones delighting in the snow.

Midwest Book Review praised the book as “very highly recommended” and wrote, “Dedicated mystery buffs will appreciate the deftly crafted characters, as well as the unexpected plot-driven twists, turns and surprises …”

The new edition is available at https://www.harlequin.com/shop/books/9781335299741_show-me-the-sinister-snowman.html. The trade- and e-book editions remain available on Amazon.

—Carolyn Mulford

Memories Sparked The Feedsack Dress

When I began writing The Feedsack Dress almost 50 years ago, I asked my mother and two sisters to talk about their memories of 1949. I’d chosen that year for the novel because my recollections and my research identified it as a time of transition for the country, our rural Missouri community, and our family.

Our discussion evoked many forgotten details and produced a major plot point.

We gathered around the kitchen table at my parents’ farm on a hot summer day. To my surprise, each of us remembered not only different movies and music but also different versions of events, including family reunions and what happened when I broke my arm. (I tested the knot in a rope I’d tied around a tree limb by sliding down it. The knot failed the test.) The discrepancies convinced me of the unreliability of eyewitness accounts, a factor I consider in writing both nonfiction and fiction.

Judy, four years younger than I, remembered the least, but even she recalled the drudgery of pumping water for the milk cows and the excitement when REA extended the electric lines past our place. Overnight my parents could milk triple the number of cows, my mother didn’t have to bear the heat of a wood cooking stove, and we could listen to Kirksville’s new radio station without fear of running down the battery and read under strong lights rather than dim kerosene lamps. Electricity improved our daily lives and increased our income.

Donna and I spent many hours on 4-H sewing projects. Our mother taught us to sew on a treadle machine, using patterned feedsacks that had contained chicken feed to make tea towels, potholders, pillow slips, and, as our skills grew, clothing—skirts, blouses, shorts, and dresses. An electric sewing machine made the work easier. New synthetic fabrics didn’t, at least for a couple years.

Unlike me, Donna loved to sew, partly because it gave her a chance to expand her limited wardrobe in an age of hand-me-downs. Five years older than I, she’d been born in the Depression, walked alone a mile and a half to the one-room school (New Hope) that my father and his mother had attended and at which my mother had taught, and become a teenager as my parents put aside every possible penny to pay off the farm they bought at the end of World War II. My big sister became a skilled seamstress. For decades she took pleasure in making clothes to wear to college and then to work as a bookkeeper. She also made clothes for others, including her kids and me.

I took special note of Donna’s difficulties in moving from a class of three in a grade school with about 15 pupils to classes of 30 in a junior high with about 500 students. She was tiny and timid, preferring to be unseen and silent. Our grade school’s limited resources and mediocre teaching hadn’t prepared her well for the tough competition. (Judy and I had an excellent teacher and went to town better prepared.) Determined to hold her own, Donna studied hard and earned membership in the National Honor Society. One test day when snow blocked the roads, she persuaded my father to take her the five miles to high school on the tractor.

A key plot point for The Feedsack Dress came to me when Donna vividly recalled ninth graders passing around slam books, often the little autograph books then popular, with mean comments about fellow students. My protagonist has to deal with those slams as she forms friendships and makes enemies.

I recalled the four of us talking about 1949 recently because my big sister, Donna Lee Mulford Helton, died February 5, 2021. Now no one shares those memories.

—Carolyn Mulford

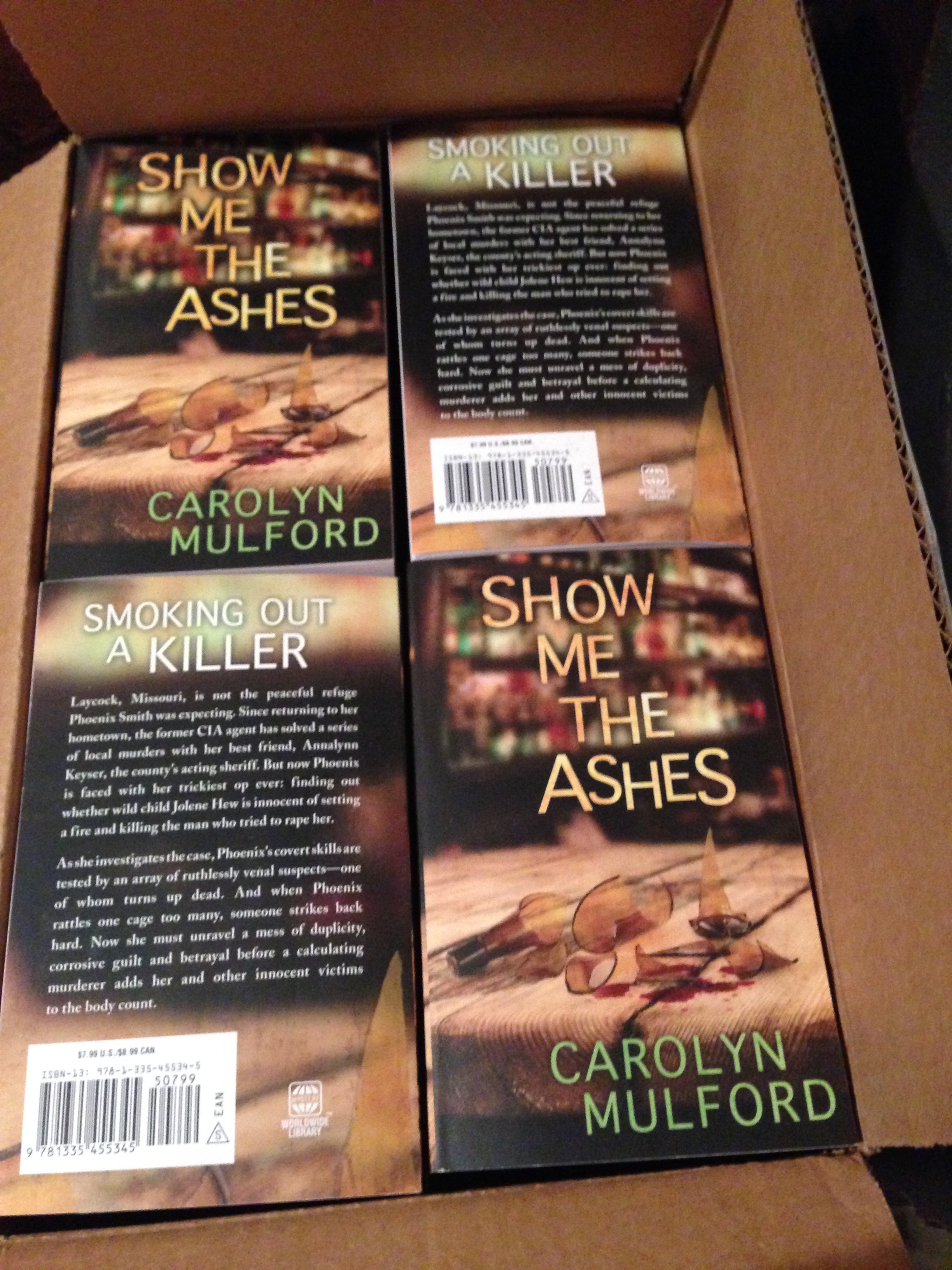

Giveaway of New Show Me the Ashes Edition

On May 7, Harlequin’s Worldwide Mystery will release a paperback edition of Show Me the Ashes, the fourth in my series featuring former CIA operative Phoenix Smith solving murders in rural Missouri.

Box of Harlequin Worldwide Mystery edition of Show Me the Ashes

In this one Phoenix and friends, including Achilles, her Belgian Malinois, take on a cold case involving a coerced plea deal (far too common), a string of disturbing burglaries, and crippling bigotr

The WM editors insisted on one editorial change from the original Five Star hardback and e-book editions: “Tramp” replaced “slut.”

The covers of the paperback and hardback editions look nothing alike, which is also true of the covers of the first three books in the series.

Another major difference is the price. The hardback edition (now out of print) listed at $25.95. The paperback sells for $7.99 (discounted to $6.39) on Harlequin’s direct-to-consumer site (https://www.harlequin.com/shop/books/9781335455345_show-me-the-ashes.html).

To read the first chapter, go to https://carolynmulford.com/mysteries/show-me-the-ashes/show-me-the-ashes-chapter-one.

U.S. residents may enter to win one of five giveaway copies by leaving a brief comment on what social or legal injustice they find most disturbing. The deadline is May 5, 2019. I will select winners randomly.

Vacationing with Jane Austen

I first read Pride and Prejudice in ninth grade. I didn’t understand it, and her humor went right by me. I read it again in an English Lit class in college and loved it.

Every few years I reread P&P, delighting in Jane Austen’s wry wit. I also have read her other five novels at least once, most of them fifteen years ago as I was planning a trip to England. I particularly enjoyed visiting Austen-related places in Bath and her last home in Chawton, where the small table at which she worked still sits by the window.

Last year I joined the local branch of the Jane Austen Society. A member heard me speak on character development in my Show Me mystery series and suggested I talk to the group about Austen’s characters. I hesitated because I lacked the time and the expertise to address this knowledgeable group, but getting to know Austen better appealed to me. I wondered if offering a novelist’s view of the great writer’s protagonists might be worthwhile.

I decided to take a mental vacation, a journey through JA’s six novels, to indulge myself and to figure out what to say. My itinerary took me from book to book in the order in which she wrote her first drafts: Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice, Northanger Abbey, Mansfield Park, Emma, Persuasion. This allowed me to observe her literary growth from age nineteen to forty-one.

Along the way, I looked for an answer to a fundamental question: Why do the six novels of a writer who died 200 years ago continue to fascinate readers?

My previous readings had produced certain assumptions, not all of them correct.

- The books remain popular because of the characters and the wit, humor, irony, and insight with JA which presents them. The characters are universal and timeless.

- Each book has the same basic cast of characters.*A young female protagonist with a difficult family but one sympathetic sister or friend and a desire to marry for love in a time when economics often determined marriage;

* A wealthy, haughty man who turns out to have a good heart, e.g. Darcy;

* A charming, handsome man who turns out to be a charlatan, e.g., Wickham (characters likes Darcy and Wickham have become a convention in most romance novels);

* An older woman who provides comic relief;

* A man who’s a bit of a fool.

* Enough family, friends, and acquaintances to have a ball.

- Plots always feature a woman without money being pressured to marry for her own and her family’s security.

- The major settings are a village and Bath.

The books differ from each other much more than I remembered. JA never wrote the same book twice.

1 Each protagonist has a distinctive personality. They aren’t just weak versions of P&P’s Elizabeth Bennet and Fitzwilliam Darcy.Each book has at least one interesting female antagonist, some of them fascinating.

- Secondary characters play similar functions in each book but are distinctive personalities.

- The plots are quite intricate. JA lays out clues of what’s to come with the care and subtlety of a mystery writer. (Perhaps that’s one reason so many mystery writers adore her.)

- The settings also have more variety than I recalled. Austen clearly disliked Bath.

Jane Austen considered villages the ideal setting, a place one where everyone knew everyone and all the residents interacted with one another. All of her books have an ensemble cast, but Austen develops some characters more fully than others.

For this journey, I intended to focus on the protagonists and how these women differ. That proved difficult. Often the villagers, particularly the antagonists, demanded equal time.

Sense and Sensibility

Jane Austen started work on Elinor and Marianne in 1795, revised it in 1797, and revised it for the last time in 1810 for publication as Sense and Sensibility. It was her first grown-up novel, one she hoped to get published rather than merely share with family and friends. In her early teens, she’d written largely to amuse, but in S&S she discussed an intellectual issue, the comparative values of sense (basically practicality and rationality) and of sensibilities (basically emotions and aesthetics). The arguments play out in the characters’ actions and reactions, in the descriptions of landscapes, and in various discussions. The theme of sense and sensibility is emphasized much more than the theme of pride and prejudice.

Two sisters are the main characters, but they aren’t Jane and her adored older sister Cassandra. Protagonist Elinor Dashwood, who is 19 going on 30, represents sense and her sister Marianne, who is 17 going on 15, represents sensibility. Sense crosses the finish line far ahead of sensibility. Over the book, both sisters change, but cautious, self-righteous, admirable Elinor modifies her thinking far less than emotional, go-for-the-gusto, pleasing Marianne does.

We know from letters, etc. that Jane hated affectation, particularly people going into raptures over music, art, or scenic views, all of which she loved. That certainly comes across in this book.

Austen’s plots grow from the characters, and the plots reveal those characters. In the best scenes, those revelations come in marvelous dialogue, including long speeches few writers could get past an editor today. Austen also does a lot of telling rather than showing, usually in the omniscient voice, and that’s truer in S&S than her other books.

Here’s a quick reminder of the S&S plot and major players. When Mr. Dashwood dies, John, his son and heir—at his wife Fanny’s urging—sends the second Mrs. Dashwood and his three stepsisters off to live in poverty. Fanny is motivated by money and the threat posed by her brother Edward’s love for Elinor. The book starts slowly with this backstory, but the early dialogue in which John and Fanny justify giving less and less to his half-sisters is hilarious and brilliant in revealing their character. Their little scene hooks the reader.

Mrs. Dashwood’s wealthy relative gives the refugees a cottage and friendship. Elinor tries in vain to keep her mother from overspending and Marianne from dismissing people she doesn’t value. Marianne declares stoic Colonel Brandon, 35, as too old to marry and falls in love with a handsome, charming, young man named Willoughby who spends beyond his means.

Variations of Willoughby appear in all the novels. He spends a lot of time with Marianne and the family, and she gives everyone the impression they’re engaged. He leaves for London and doesn’t write or return. Elinor is the only one not surprised.

The sisters go to London with Mrs. Jennings, a sociable widow of a rich tradesman, although Marianne looks down on her. Initially Mrs. Jennings serves as the comic relief character, but she develops into one of the book’s most admirable people. In London, Marianne learns Willoughby has married for money and makes herself ill—as she thinks a person of sensibility should—by not eating or sleeping. She’s extremely self-centered (she’s 17) and inconsiderate.

In contrast, Elinor hides the pain she’s suffering from a similar loss and remains courteous despite all provocations. She’s astounded when Lucy Steele, a rather desperate young woman who lives by sponging on relatives and friends, reveals she and Elinor’s Edward have been secretly engaged for four years. (JA slips in women’s lack of power and the need to survive by their wits in each book.) The verbal sparring between Elinor and Lucy shows how intelligent both are and what self-discipline Elinor has. Their exchanges are the highlight of the book for me. Edward comes on stage, but we see little of him in the book.

Elinor and Marianne start home, but Marianne becomes very ill and they stay at a friend’s home. Colonel Brandon rides off in a storm to bring their mother. In a major surprise and one of the best scenes in the book, Willoughby shows up to explain why he couldn’t marry the woman he loved. That scene makes him one of the best-drawn of JA’s male characters.

I suspect that a publisher refusing to look at S&S in the early 1800s was a good thing, that JA’s later revisions made it a much better book.

Pride and Prejudice

Austen wrote the first drafts of First Impressions in 1796-97, when she was 20 and 21, and spent some time revising what became Pride and Prejudice after she sold S&S in 1810. One thing writers learn is that the title makes a difference in sales, and the change was important. During her lifetime, her name never appeared on her novels. They were “by a lady.” The parallelism of Sense and Sensibility and Pride and Prejudice helped link the books in the minds of readers and encourage sales.

Reading S&S and P&P back to back showed me Austen made a great leap forward as a writer. In terms of structure, characterization, and wit, P&P is a much stronger book than S&S. The second book is superbly crafted. The opening chapter grabs you and propels you into the story. JA does much more showing, mostly through wonderful dialogue, and she gives more in-depth portrayals of her village’s secondary characters. She creates some of her best comic relief characters.

I’m certain the revisions were crucial. No manuscript is that good without several rewrites. By 1810, Austen had the distance to read her own work with an editorial eye. She also had collected readers’ comments on S&S (novels rarely received reviews), and the criticisms must have suggested such changes as more dialogue and less exposition. One major craft advancement is her excellent handling scenes with multiple people.

Besides, in a letter to her older sister Cassandra, JA’s her first and most trusted reader, JA wrote that she had “lopped and chopped.” P&P is her most tightly written book, though Emma comes close. We know that by the time she wrote the opening chapters of the never completed The Watsons, she was working from outlines and character sketches. She probably was doing that from at least the first draft of P&P.

A letter to Cassandra also tells us that Austen considered Elizabeth Bennet her best protagonist and possibly the best heroine in contemporary novels.

Elizabeth Bennet and Fitzwilliam Darcy remain among the best known characters in English literature. Film adaptations have made them familiar to many people who never read 19th-century novels. Elizabeth is flawed but feisty—and very articulate and outspoken. While she relies too much on first impressions, she learns to revise her hasty judgments, as in accepting that Charlotte is quite content in marrying a boring man (partly because she finds ways to avoid his company) and that Mr. Bennet hasn’t been a good parent. I suspect Elisabeth is the woman Austen would like to have been.

Elizabeth’s quieter, prettier, older sister Jane strikes me as likely to be the closest to Cassandra of any of the major secondary characters. Jane Bennet expects the best from people, but she senses wickedness in the charming and glib Wickham, a classic con man, before others do. He’s one of the few characters with no redeeming virtues.

Darcy is Austen’s most popular male character. I find his treatment of Elizabeth goes beyond pride to an unaccountable social awkwardness. But as Elizabeth said, he looked more appealing once she’d seen Pemberley, his prosperous estate. The remark is both a joke (wealth makes men more attractive) and a truth in that seeing how much his servants respect and like him gives her new respect for him.

The major comic relief characters are some of Austen’s most memorable, partly because they’re really funny and partly because they offer more than humor. The pompous, snobby Lady Catherine runs her estate herself and speaks on the importance of education and the unfairness of the entailment system. The obsequious Mr. Collins, her curate, stands to inherit when Mr. Bennet dies. Mr. Collins comes to the Bennets looking for a wife with the kind-hearted view that since he’s the heir, he should help them out by marrying one of the daughters.

For me and a lot of other writers, P&P is one of the few books worth reading multiple times. JA’s distinctive voice rings strong, and her wit and insight in portraying recognizable people delights again and again.

Northanger Abbey

The book Austen wrote at 23 harks back to her teenage work, written for laughs. Northanger Abbey is a farce, a send-off of the formulaic Gothics popular then. Yet it also has some scenes as good as anything in Pride and Prejudice.

Northanger Abbey has an odd history. She wrote it as Susan in 1798-99, revised it in 1802, and sold it in 1803. The publisher held it, and she finally took it back in the spring of 1816. Somewhere along the way it became Miss Catherine. Her brother changed the title to Northanger Abbey for publication after her death in 1817.

I’ve read that she revised it and that she didn’t revise it in 1816. By then she was not feeling well and was working on other books. Judging from the writing and the content, my guess is that she polished the scenes in Bath, the best part of the book, and barely touched the later portion at Northanger Abbey. It has less humor, for one thing. Certainly she failed to develop Eleanor’s character and to foreshadow her marriage, and that’s not typical Austen. Also she addresses the reader more in this book than in her others.

Her protagonist is Catherine Morland, a naïve but intelligent curate’s daughter in rural England. She reads and takes seriously Gothic novels. She’s 17, which Austen apparently sees as the age when young women are most likely to do stupid things. When the book begins, Catherine has no street smarts and is a terrible judge of people. When the book ends, she’s learned a lot but still doesn’t have the savvy or sophistication of the other protagonists.

Austen begins by telling the reader what Catherine isn’t in terms of the conventions of Gothic novels. The description of Catherine as a child reminded me of something I’d read about Jane as a child. Little Catherine was plain and liked boys’ play, including rolling down hills. Until 10 she was noisy and wild and dirty but kind. At 15 she was much improved—“almost pretty.”

Her wealthy neighbors, the Allens, invite her to go with them to Bath for six weeks, probably because Mrs. Allen doesn’t know anyone and wants someone to go with her to the shops and to the gatherings at the Pump Room. Mrs. Allen, the comic relief character, sees everything in terms of fashion. Catherine asks her if it’s proper to go driving with a man, and Mrs. Allen worries about the wind messing up the girl’s dress.

At the Pump Room, described in considerable detail, they meet Mrs. Allen’s old school friend and her daughters. Both women talk, neither listens. Isabella, the oldest and prettiest daughter, latches onto Catherine as her noncompetitive wing woman in an ongoing hunt for a man with money. Catherine is so unworldly she protests when Isabella flatters her and welcome the manipulative Isabella’s false friendship.

Catherine dances with a young curate named Henry Tillney. He teases her because she’s so naïve and so involved in Gothic novels but recognizes that she’s unusually kind. He’s a bit of an intellectual snob and likes that she listens to what he says and laughs at his jokes. He’s nothing like the distant Darcy.

Isabella succeeds in winning the love of Catherine’s brother, James, an Oxford student who seems more affluent than he is. JA spends few words on James.

Isabella’s brother, John, courts Catherine because he thinks she’ll inherit money from the childless Allens. John is a buffoon and a braggart, which Catherine recognizes when she sees his horse goes half as fast as he claims. She tries to avoid him and spend time with Henry and his shy sister. She also meets their dictatorial, money-hungry father, who mistakenly thinks she will be wealthy and invites her to visit Northanger Abbey. Meanwhile Isabella flirts with the handsome older son, Captain Tillney, the book’s bad guy.

One of the things that’s different about the protagonist of Northanger Abbey is that she doesn’t have another woman to guide her or for her to guide. She’s out there on her own and has to find her own way.

Mansfield Park

Coping with deaths and other family problems interfered with Austen’s writing for several years. She planned and wrote a few chapters of The Watsons in 1804-1805, dropped it, and did little but revise her first two books until 1810 when she sold S&S.

In February 1811 she began work on Mansfield Park, which she finished in May 1814. I think she moved a little too quickly on publishing this one, that it could have used a little lopping. It has a darker tone than any of her books. I suspect she didn’t enjoy writing it as much as she did the first three. She’d called Pride and Prejudice “light and sparkly.” Perhaps she felt she needed to write a more serious book.

The cast of characters suggests Austen had lost some of her optimism about people. The major comic relief character, for example, is downright cruel. A lot of the secondary characters behave not just thoughtlessly and selfishly but destructively.

The protagonist differs in that she’s intimidated by everyone around her. She’s so physically weak she can’t go on long walks (important in JA’s fiction and her life), does not function as part of a family, and for an Austen protagonist, is inarticulate. She resembles the Fanny in Lady Susan, JA’s teenage epistolary manuscript. That Fanny is roguish Lady Susan’s mousy, put-upon daughter. When she finally triumphs, we’re not sure whether it’s mostly luck or a well-developed survival instinct.

Fanny Price comes from more modest circumstances than other protagonists. She’s the daughter of a drunken sailor and a woman who married beneath her. Her wealthy, reserved uncle and lazy, once-beautiful aunt take her in at age 10 at the urging of another aunt, Mrs. Norris. This nasty woman apparently wants someone around who’s lower on the totem pole than she is.

Taken from a large, noisy family and brought into the mansion at Mansfield Park, Fanny is scared, cowed, and lonely. She tries to make herself useful and invisible, and succeeds in both. Mrs. Norris and the two female cousins mistreat her, mostly with verbal abuse, but she gradually becomes indispensable, much like a servant, to her lazy aunt. Only cousin Edmund, who will become a curate, sees the child’s misery and is good to her.

So Fanny becomes a modest, mousy, moralistic, passive, always proper teenager. No one ever thinks about including her in balls, and she’s doesn’t object, partly because she’s not sure she’s strong enough to dance and partly because she views herself much as they do.

On the plus side, she’s extremely observant and skilled at reading character, traits the powerless develop in self-defense. As the self-absorbed slightly older female cousins make a mess of their lives and leave the home, Fanny receives more attention from her uncle and aunt and gains some confidence. To her and everyone else’s surprise, she becomes pretty and is a big hit at a ball. (Where did she learn to dance?)

Naturally Fanny secretly loves her good cousin, Edmund. He’s quite fond of her in a brotherly sort of way. He’s in love with the most interesting woman in the book, the wealthy, beautiful, charming, talented Mary Crawford. She’s taking a break from her usually active social life in the cities and staying with her amiable half-sister, the local curate’s wife. Mary initially likes the older brother, largely because he’s the one who will inherit Mansfield Park, but she comes to love Edmund—conditionally. He either has to inherit or take up a profession that pays well.

JA develops Mary more than most antagonists. She is a multidimensional character. For one thing, she sympathizes with Fanny’s position, treats her well, and teaches her little things that contribute to her growing self-confidence.

The most interesting male character is Mary’s brother, Henry Crawford. He’s wealthy, handsome, charming—a great catch whom the two female cousins pursue. Fanny sees how immoral he is and doesn’t like him. Her disdain challenges the Lothario, and he tells Mary he will make Fanny love him. His sister discourages him from hurting Fanny, but he pursues her and falls so in love he proposes.

To his and the family’s disbelief, she turns him down and resists all pressure to change her mind. Henry appears to have reformed because of his love for her, and even persists after he sees her unappealing lower-class family while she’s visiting them in Portsmouth. She begins to regard him more highly, and I was rooting for this guy—a lot more fun than Edmund. But Harry returns to his immoral ways and runs off with Fanny’s married cousin.

Emma

Austen began her fifth book, Emma, in January 1814, not long after she’d submitted Mansfield Park to her publisher. But Emma has a much lighter mood and a much less villainous cast of characters. As in Northanger Abbey and P&P, Austen was having fun.

From what she told her family, she knew that many readers wouldn’t like Emma as much as her other main characters, but she did. When I read the book years ago, I became annoyed with Emma, but I enjoyed the book far more on this rereading. It’s really well done, second only to P&P in integrating plot and character.

Emma Woodhouse is the most privileged, self-confident, and mistake-prone of JA’s protagonists. She also dominates the book more than other main characters.

The book’s first sentence tells us Emma is “handsome, clever, and rich, with a comfortable home and happy disposition.” She’s 20, which Austen regards as maturity. Her mother is dead and her older sister married, so she manages her father’s household. She’s the village’s Queen Bee with complete confidence in her abilities as a matchmaker and in overseeing the social goings-on in Highbury. The entire book, by the way, is set there. All of the other books have more than one setting. Emma’s arrogant and snobbish and impulsive and thinks her judgment better than anyone else’s. She lacks the self-doubts of all the other protagonists.

Another major difference: She’s happy with her life as a wealthy single woman and has no intention of marrying.

Two things make her a sympathetic character: She’s very good to her difficult father and she’s intends to help people even as she’s messing with their lives. Much of the humor comes out of those two factors.

Mr. Woodhouse is the major comic relief character, a role usually given to a woman. He’s frail and rigid in his ways. A lot of the humor comes from his hypochondria and his concern for his diet and for cold drafts, etc. He warns others about his health concerns, and Emma tries to protect his guests from such things as eating nothing but gruel in the evening. He’s funny, but he’d be hard to live with so Emma’s patience speaks very well for her.

The leading man, George Knightley, is a wealthy neighbor, Emma’s brother-in-law’s brother, and a longtime trusted friend and advisor. He’s about 35, an age Austen favors for men, and acts like an uncle. He’s fond of Emma and feels it his duty to point out her flaws as her father and no one else does. He pretty much expresses Austen’s and the readers’ judgments of Emma’s follies. He’s not particularly exciting, but he’s a good man who values and cares for people regardless of class. And he has no interest in being a curate.

In fact, the curate in this book, Mr. Elton, turns out to be a bit of a jerk. His bride is even worse.

The other major male character is Frank Churchill, the handsome, charming, well-educated young man who has been made a rich relative’s heir. He flirts with Emma and is obviously not as good as he seems, but he’s not a villain like Wickham or a cad like Henry Crawford. Instead he’s covering up his secret engagement to Jane Fairfax, a poor but beautiful, accomplished, and reserved young woman whom Emma sees as a threat to her role as Queen Bee. Unlike Mary Crawford, Jane turns out to be quite principled.

In this book, Austen gives us subtle clues to things Emma’s missing, such as Churchill going all the way to London for a haircut—a cause of great comment in the village—and an anonymous person giving Jane Fairfax a piano a few days later.

We see great changes in the protagonist, much like Catherine in Northanger Abbey.

Persuasion

Austen’s last novel was Persuasion. She began it in August 1815 and had it ready except for a final polish a year later. By then she wasn’t very well, and she never got back to it. Despite such shortcomings as overusing the name Charles and a long chapter revealing the villainy of the protagonist’s suitor being too much of an info dump, it’s a very good book.

Persuasion is shorter than the others, focusing more sharply on the main story. Some believe she intended to write another section. I doubt that for two reasons: She’s concluded the main story, and she wrote twelve chapters of a new book before becoming too ill to work.

The main characters, Anne Elliot and Captain Wentworth, and several of the secondary characters are portrayed with great subtlety, sympathy, and softness. Austen populated Mansfield Park with many dislikable characters. She populated Persuasion with people you’d like to know, notably the older married couples. They don’t fare so well in other books.

I noticed an oddity in her comic relief characters, something she might have tempered in a final pass. The one-note portrayal of vain, arrogant, extravagant Sir Walter, Anne’s father, is so over the top that he’s a caricature. His oldest daughter, Elizabeth, is much the same. His youngest daughter, Mary Musgrove, is no more likable but is much more realistic and much more developed. The fact she’s the baby of the family may be relevant to her being such a spoiled brat and so hungry for attention.

Anne, 27 or 28, is Austen’s oldest and most mature character. At the cut-off age for marriage, she’s the most fully formed personality. Humble and reserved, clever and practical, she’s dismissed by all her family members but valued and liked by others. Again and again, she tales sp;ace in being useful, as when she plays the piano for hours while others dance even though she loves to dance. She had that in common with her creator.

Austen told her niece Fanny, “You may perhaps like the heroine, as she is almost too good for me.”

That goodness, her overdeveloped sense of duty and honor, led her to make a huge mistake. She allowed her mentor to persuade her to reject the proposal of the penniless young naval officer whom she loved deeply. Her father despised Frederick Wentworth because of his lack of wealth and status. When the book opens, Anne has been suffering for letting others sway for eight years. She’s “lost her bloom.”

When newly well-to-do Captain Wentworth returns, Anne hears from obtuse sister Mary that he’s said Anne has changed so much he hardly knew her. The rest of the book, of course, shows them finding their way back together.

Austen had brothers in the navy, and in this book she has four naval officers who are portrayed quite favorably. Wentworth is a bit too good to be true, but that fits with the portrayal of Anne.

Austen’s maturity as a woman and her mastery of craft come out in Persuasion. The interplay of six characters during their long walk and the drama of careless Louisa’s fall show considerable insight and technical skill.

So what did I learn during my mental vacation? Before rereading the books in sequence over about three months, I assumed Jane Austen developed her characters directly from people she knew even though her relatives claimed that only two or three of her characters were based on real people. Now I believe them. I think she was an extremely astute observer and eavesdropper (most writers are), but part of the fun for her as a writer was to create her own distinctive villages.

She drew on her own experiences but didn’t portray herself in any of her protagonists. No one person could have been Catherine in Northanger Abbey, Emma, and Elizabeth Bennet, her favorite. That doesn’t mean bits of her weren’t in all of them.

Jane Austen gave us some of the most memorable protagonists and antagonists in literature, and they’re people as recognizable today as they were 200 years ago. That’s why we’re still reading her books.

I enjoyed spending time exploring Jane Austen’s villages.

My 2018 Novel Work Plan

On this day of hope, I like to plan my writing agenda for the coming year.

January is prime writing time. The weather discourages me from going out, and the lack of distractions encourages creativity. I also sleep better snuggled under layers of covers. Tomorrow I stop thinking about the second book in my new mystery series at random moments and start serious work on it. The book, which takes place at a storytelling festival, will consume much of my work time the rest of the year.

By the end of February, I expect to have completed a solid draft of the first seven or eight chapters, the most difficult part of the book. At that point in the manuscript I can automatically visualize the settings in which my new characters interact and understand the difficulties (personal and investigatory) my ongoing characters must deal with.

Taxes and cabin fever interrupt the workflow a bit in March. That’s also a time in the manuscript when I’m questioning my pacing and worrying about too much dialogue and not enough action.

In April I’ll be dealing with the doubts of March, updating my narrative to reflect the unexpected development of minor characters or the appearance of unanticipated clues. Novels, like life, rarely go as planned.

Conferences, holidays, and spring pull me from the computer in April and May. In 2018, May is likely to be one of my least productive months. I’ve planned a mental vacation, in this case preparing a talk on how Jane Austen reveals her protagonists’ characters. I’ll enjoy the research and analysis, but both will require considerable time and concentration.

An advantage of this diversion is that I’ll come back to my manuscript, which should be about two-thirds of the way done (in first draft), in June with a fresh eye.

In July, I hope to approach that final push. That’s when the writing goes fast.

If all goes well, in August I’ll complete draft one and do cleanup work, making sure the clues fall in the right place, characters act consistently, any factual holes are filled, and weak words become strong.

My critique group will be giving me feedback as I proceed, but in September I’ll ask the members for an overview and send the draft to two or three other readers. Then I’ll play a little while, and perhaps work on a short story/novella with the characters from my Show Me series.

October will be my month to take care of the problems my readers note and, finally, to read the manuscript aloud and give it the final polish.

In November I should have the manuscript ready to go. That leaves December to finish some of the things I’ve neglected the rest of the year.

Will my year really go this way? I’ll let you know in 2019.

—Carolyn Mulford

When Your Publisher Closes

The publisher of Thunder Beneath My Feet is closing shop December 31, 2017. Both the e-book and print editions will disappear from online bookstores. In 2018, my garage will hold most of the remaining copies of my novel about the devastating New Madrid earthquakes of 1811-1812.

Many writers face this problem. Small publishers often go out of business after a few years of struggle. Big ones discontinue imprints that don’t meet sales targets. One friend’s mystery won an Agatha a couple of days after she heard her big-name publisher was abandoning the imprint. Another friend has seen three of her publishers go under. My Show Me series publisher, a small part of a huge conglomerate, announced to authors in early 2016 that only mysteries already under contract would be published. I sold the fifth book in my series, Show Me the Sinister Snowman, to another publisher and moved on to a new series.

The Thunder publisher, a small independent, notified her authors of the pending closing in November 2016 and suggested they look for another publisher or self-publish. She preferred to write and farm. Who can argue with those priorities?

Now what?

My first thought was to self-publish the book. I loved writing Thunder, and readers have given it great feedback. I brainstormed for a distinctive publishing name, one short enough to fit on the spine and visual enough to suggest a logo. The company name would also need to work if I wanted to self-publish mysteries. Darned tough to come up with a winner.

Over the last ten years I’ve learned that successful publishing involves not only having a quality product but also a good marketing plan and an economically feasible way to distribute books to bookstores and libraries. Few self-publishers live by Amazon alone.

Having earned my living as a freelance writer and editor for some 35 years, I know how much time and effort the business side can take. Did I want to put writing aside to spend time (and money) on marketing and distribution?

The marketing and distribution challenges

I worried about penetrating the most obvious market, Missouri schools, something the publisher hadn’t tried to do and I hadn’t accomplished.

Many writers promote sales, and earn money, by giving programs at schools. That works well if you have several successful middle grade books. I don’t, and I’m not trying to build a career writing MG/YA books. Besides, I had no contacts.

I submitted Thunder to for possible inclusion in the Missouri State Teachers Association’s Reading Circle Program. The reviewer told me she was recommending it, but the list of approved books still hasn’t come out.

In my first efforts to sell to schools, I became a vendor at state conferences of history teachers and school librarians. The librarians particularly liked to my pitch, but they pointed out that they preferred to buy hardbacks. Paperbacks don’t last long in school libraries.

If I were going to publish a new edition, hardbacks seemed the way to go. I did some pricing. The per unit cost goes down as the number of copies go up. Small print runs would mean raising the price of the book to more than most libraries would pay.

One key problem in marketing to schools was the failure to send review copies to such essential professional publications as School Library Journal. (It has precise requirements on submission times of review copies and on national distribution.) Without favorable reviews in professional publications, librarians hesitate to buy. I doubt anyone would consider reviewing a self-published second edition.

National (and regional) distribution to bookstores and libraries constitutes a major problem for both small publishers and self-publishers. Many bookstores dislike (even refuse) to deal with Amazon or Ingram, preferring to buy through such distributors as Baker & Taylor.

Online sales, particularly of e-books, allow some self-published books to flourish, but I didn’t see that as the case for my MG/YA historical novel. Most of my sales have been print copies.

Maybe later

For now at least, I’ll let Thunder Beneath My Feet go out of print. If a demand develops, I can always self-publish. If a publisher with marketing savvy and distribution capabilities wants to pay me to publish a new edition, great.

Meanwhile, I have a couple of dozen copies in the garage. If you want to buy one or more, contact me.

—Carolyn Mulford

1811: Earthquakes Flood Little Prairie

The first earthquake threw the 150 or so residents of Little Prairie out of their beds. The ground roared, moaned, and rumbled. Strange lights flashed from the earth. A dense vapor blacked out the stars.

Thus, at 2:30 a.m. December 16, 1811, began the New Madrid earthquakes, some of the most powerful and far reaching quakes ever experienced in North America. Three major earthquakes, several aftershocks almost as powerful, and at least 1,800 notable tremors terrified the region and disturbed sleep as far away as Quebec over the next three months.

The little Mississippi River frontier village lay near the epicenter (the northeast corner of present-day Arkansas) and suffered some of the most severe damage, forcing the entire town to flee for their lives.

The refugees reported that the shock at 8 a.m. was even worse. The ground quivered and writhed. Cracks appeared in the earth, and steamy vapor, blood-temperature water, and mud blew from them. The earth opened and shut. Water spouted higher than the trees.

Later that morning, a chasm 20 feet wide opened in the town. Quicksand and water gurgled up, and a warm mist carried the smell of brimstone.

The tough citizens of Little Prairie began to pack a few light possessions.

At 11 a.m. a huge upheaval beneath the town lifted and heaved it. A dark liquid oozed from the ground, and water spouted 10 feet high. The town began to sink. Trees, houses, and even the mill went down.

Everyone ran in the warm waist-deep water, children on adults’ shoulders. They waded through the water for eight miles before they reached high ground. Swimming beside them were wolves, possums, snakes, and other animals.

Days later, their hope and food supplies exhausted, they walked north to New Madrid.

If I ever write a sequel to Thunder Beneath My Feet, I’ll find out where they went from there.

—Carolyn Mulford

Prime Promotion Season Ends

Bookies Book Group

Part of a novelist’s job is promoting, and promotion took more time than usual this fall. After all, the approach of winter was a good time to talk about my last book, Show Me the Sinister Snowman.

Reminder: Still time to buy a copy as a Christmas gift.

Most of my promotion is more subtle than that. For example, in October I took a mental vacation from being an author and prepared a lecture on novels that have had an impact on society for the local Osher Lifelong Learning Institute. Naturally I gave attendees an opportunity to buy copies of all seven of my novels.

October is prime conference time. I served as a panelist and a panelist/moderator with some of my favorite writers, including Kent Krueger, at Magna cum Murder in Indianapolis. That enjoyable (and tax deductible) annual event offers opportunities to have in-depth conversations with other writers and with readers.

The last weekend in October, I split my time between the regional library’s Local Authors’ Day and the innovative ShowMe MasterClass co-sponsored by the Columbia Chapter of the Missouri Writers’ Guide and Mizzou Publishing. My contributions to the latter were mentoring two aspiring novelists and speaking on polishing a manuscript.

In November I used my leftover research on Thunder Beneath My Feet to give a talk about the disastrous New Madrid earthquakes of 1811-1812 at the Senior Center. I’m afraid my descriptions and anecdotes alarmed them about the quakes to come (no one knows when). Several vowed to modify their home insurance to include earthquake coverage.

A week later, I covered some of the same material and answered lots of questions in a long conversation with members of the Bookies, an enthusiastic book club. I never get tired of talking with readers.

Off and on through these and other events, I worked on polishing the manuscript of the first book in a new series. Appearances over and manuscript finished, I’m looking forward to my favorite season, working on my next mystery.

—Carolyn Mulford

Great ShakeOut Falls on October 19

More than 52 million people—students, hospital workers, business employees, etc.—will take part in International Shakeout Day Thursday, October 19, 2017.

In the United States, the Great Shakeout earthquake drills start at 10:19 a.m. Well over 2 million of the 18 million Americans learning how to react to quakes live in the large New Madrid Seismic Zone. There three of the nation’s most powerful earthquakes, plus some 2,000 aftershocks, took place in 1811-1812.

But you know that if you’ve read Thunder Beneath My Feet.

Keep in mind three basic steps when an earthquake begins.

- Drop onto your hands and knees so you won’t fall down and can crawl to any nearby shelter.

- Cover your head and neck with one arm and hand to protect you as you crawl under a table, desk, or anything else that will protect you from falling objects. If you have no shelter nearby, crawl to an interior wall.

- Hold on to your shelter but be ready to move if it gives way.

You can download drill manuals for schools and businesses and find information on what to do in various situations on shakeout.org. For example, if you’re in bed, stay there and lie face down to protect your vital organs, cover your head and neck with a pillow, and hold on to your head and neck with both hands until the shaking stops.

I’d always heard to stand in a doorway, but the site says you’re safer under a table.

Even if you don’t do a drill, check out the information and keep it in mind just in case.

—Carolyn Mulford

Reunions and Life Stories

Last weekend I attended my 60th Kirksville Senior High School reunion. There I found myself surrounded by joyful former classmates and a rich tapestry of life stories.

This three-day reunion reminded me that one source of ideas for my Show Me mysteries was our surprisingly happy 45th reunion. Interactions with old friends made such a deep impression that they influenced me a couple of years later when I began developing the ongoing characters for my series.

I created three women who grew up together, led very different lives, and reunited in the hometown as each faces a personal crisis. The protagonist juggled a dangerous double life in Vienna as a CIA covert operative and comes home to heal with her closest childhood friend, a civic leader who never left. The third friend gave up her dreams of Broadway to further her peripatetic ex-husband’s business career.

Like many small towns, Kirksville didn’t offer enough economic opportunity or cultural appeal to hold most of the 123 graduates of the Class of 1957. About 75% went to college before scattering across the nation. One of the most common occupations was teaching, but someone did almost any kind of job you can think of.

The organizers asked me to welcome the 40 classmates and their family members who came from 14 states. Confession: I thought by welcoming they meant to greet people at the door and give them nametags. On Saturday, I realized I’d agreed to give a short speech that night. I’m a writer. I wrote a speech, or at least made notes.

Here’s approximately what I said.

Coming into the room last night and seeing all those joyful, smiling faces, I thought what a lucky bunch we are. Lucky to be here at all 60 years after graduating, and lucky to be here with each other. Looking at you, I see the faces of 1957, teenagers who share memories of an important time, those self-absorbed years when we were figuring out who we were going to be.

Memories of those years have faded, though some events remain clearer than what happened a few weeks ago. I wondered what memories everyone shares. One must be the frantic Mardi Gras season where the classes competed to raise the most money and have their class candidates named king and queen. Everyone contributed, often with unique fundraising ideas. Another would be building homeroom homecoming floats, pretty and clever presentations far more entertaining that those I see in homecoming parades now. And then we had the campaign to pass the bond issue for a new high school

Some of the sharpest memories for each for us surely involve our favorite activities—playing on a school or intramural team, rehearsing with the marching band, preparing to sing in the chorus or play in the orchestra at a Christmas program, taking the stage in a school play, serving on the student council, putting together the many pieces of the yearbook, taking part in the Roman Banquet in which the Spanish class served the conquering Latin students, traveling to Chicago with Masque and Gavel to see a big-time play and hear Tony Bennett at a real night club.

KHS offered us opportunities to explore many interests. For me, the big one was co-editing the school newspaper with Phyllis. We had a lot of fun and a lot of freedom. The experience confirmed and strengthened my desire to become a writer.

We were lucky in having excellent teachers. They went far beyond their job descriptions to counsel, coax, and coerce us to accomplish more than we thought we could. Perhaps their great example contributed to so many of the class becoming teachers.

We’ve been lucky to have Jeanne, Dorothy, and other classmates willing to organize five- and 10-year reunions for decades—and to coax and coerce classmates to come.

For me, one of the most heartening things about our reunions is this: Each reunion we seem to appreciate each other more. We had cliques and other things that set us apart in high school, but the divisions have vanished over the years. I haven’t seen so many people smiling at each other since our last reunion.

Last night as I caught up with old friends, the writer in me thought what a treasure trove of human experience had gathered. I wanted to hear about each person’s life. We’re a living anthology of life stories, and the common thread of those stories is the experiences we shared as the Class of ’57.

If you’ve taught, you’ve seen a class form a group personality. What was our group personality? I can give a partial answer: We welcomed challenges, and we worked together to meet them. Now, 60 years later, more than half of the survivors cared enough about each other to make the effort to come here.

We are a lucky bunch.

—Carolyn Mulford