Mark Twain wrote of the glory of piloting steamboats in the mid 19th century in Life on the Mississippi, but in December 1811, the crew of the first steamboat on the river feared death on the Mississippi.

The New Madrid earthquakes turned the journey of the New Orleans from an adventure into a nightmare. Designed by Robert Fulton and built in Pittsburgh by Nicholas Roosevelt, the New Orleans and its crew carried the burden of proving a steamboat could navigate the Ohio and the Mississippi rivers from Pittsburgh to New Orleans.

A clever engineer but unreliable businessman, the great-grand-uncle of Theodore Roosevelt already had surveyed the route by flatboat. The six-month, 1,100-mile float served as a honeymoon trip with his teenage bride, Lydia. She was the determined daughter of U.S. Capitol architect Benjamin Latrobe, one of the groom’s business associates. After completing the voyage in 1810, the Roosevelts returned to New York, where she gave birth to a baby girl.

In October 20, 1811, the three Roosevelts and their crew and servants left Pittsburgh on the New Orleans. Ten days later, at Louisville, Lydia gave birth to a son on the steamboat. They had to wait until December 8 for the Ohio to rise high enough the steamboat could run the Falls of the Ohio below Louisville. Roosevelt sold rides on the steamboat while they waited. Then they took a layover.

The delay may have saved their lives. The first earthquake occurred while they were moored on the Ohio, which didn’t experience the reversal of water flow, the creation of temporary waterfalls, and some other severe effects suffered on the Mississippi. The steamboat crew didn’t know what had happened or where the turbulence originated.

The Roosevelts’ large Labrador, Tiger, felt the shakes sooner and more keenly than the people on the boat did. He, like the yellow cur in Thunder Beneath My Feet, gave the people warning signals. The sturdy boat’s size lessened the shakes’ effect, and the noise of its engines masked the rumblings. Roosevelt went ashore to study the damage at the home of John J. Audubon but chose to go on to the Mississippi. Once on the great river they had little choice but to continue.

Native Americans, and some others, thought the “fire boat” or “devil boat” had somehow caused the earth to shake. The steamboat, which could travel eight to ten miles an hour, had to outrun war canoes by outlasting the paddlers. Going ashore to cut wood for fuel or to hunt game called for great caution.

As described in TBMF, Roosevelt planned to dock in New Madrid December 19, three days after the first earthquake, to take on supplies, but the shocks and shakes and the subsequent tsunami on the river and fires on land had devastated the town. Most residents had fled, and several who hadn’t begged to board the steamboat. The New Orleans moved on without them.

The worst was yet to be for those on New Orleans. The shocks and shakes changed the river, submerging large islands, moving sandbars, dissolving bluffs, altering channels. The official map and Roosevelt’s notes from the flatboat trip no longer guided travelers. Sometimes the river quickly rose several feet, and the current ran faster than usual.

Trees threatened them night and day. Newly fallen trees clogged the channel, and long-submerged trees popped up from the river bottom. The pilot kept the boat away from shore so tall trees couldn’t topple on them. Fear gripped everyone, and the rivermen, famous for their singing and banter, fell silent.

A favorite family story tells of one night, after a rare quiet day, when the New Orleans anchored on an island. Jarring and the sound of objects grating against the boat woke Lydia. Sometimes the entire boat trembled and she heard scratching and water gurgling. She thought driftwood bumping against the boat caused the noise.

The next morning, the island had disappeared. At first the crew thought the current had broken the mooring and pushed the heavy boat into a broad section of the river. Then the pilot recognized landmarks and realized the steamboat remained moored in place, but rising water had completely covered the island. They had to cut the mooring rope to free the boat and avoid being submerged.

Many smaller boats didn’t fare as well. An unknown number of people died on the river.

The steamboat reached New Orleans January 10, 1812. The completion of the treacherous journey proved the viability of steamboats on the Mississippi and introduced a new era in frontier transportation.

—Carolyn Mulford

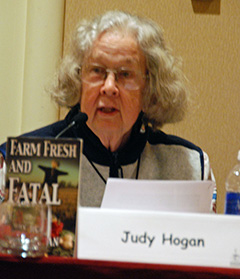

Poet, novelist, memoirist, writing teacher, and activist, Judy Hogan draws on life experience for everything she writes. To see the range of her writing and sign up for a chance to enter a giveaway of her latest mystery, Haw: The Second Penny Weaver Mystery, visit her page on GoodReads.com. The giveaway ends April 26.

Poet, novelist, memoirist, writing teacher, and activist, Judy Hogan draws on life experience for everything she writes. To see the range of her writing and sign up for a chance to enter a giveaway of her latest mystery, Haw: The Second Penny Weaver Mystery, visit her page on GoodReads.com. The giveaway ends April 26. Mainly, make yourself happy. Enjoy it. Persist, learn, read, and never give up.

Mainly, make yourself happy. Enjoy it. Persist, learn, read, and never give up.