When The Feedsack Dress came out in 2007, I started a blog on Typepad that focused on life during the late 1940s and early 1950s. I stopped posting there in 2012, but you can still link to The Feedsack Kids. I’m posting some new blogs and my favorite old ones here.

Category Archives: Uncategorized

Celebrating Jane Austen’s 250th Birthday

This year Janeites around the world are celebrating Jane Austen’s 250th birthday (December 16, 1775). Although she wrote only six polished novels before her death in 1817, she has become one of the most popular novelists in history. (If Pride and Prejudice is the only title you can remember, refresh your memory at https://carolynmulford.com/writing/vacationing-with-jane-austen.)

She may be more popular now than ever. That’s partly because the movie and TV adaptations of her books over the last 30 years have drawn and delighted readers not doing assignments. Another factor has been the proliferation of novels imagining the life of Austen’s characters and of contemporary people from around the world in plots roughly paralleling one of hers.

Writers surely must rank among Austen’s most enthusiastic readers. The woman wrote brilliantly about her time with characters like people we know today. Some poor souls have dismissed her as “only” a romance writer or novelist of social manners. She actually offers up biting social commentary with devastating humor. She also took novels in a new direction and had developed superb craftmanship by P&P.

Each novel features a distinctive protagonist, with the wealthy and wildly over-confident Emma (modernized in the movie Clueless) following the impoverished and insecure Fanny of Mansfield Park, Austen’s longest, most complex, and least-loved novel.

She doesn’t repeat secondary characters either. Even her “bad” women and men, as essential to her plots as a murderer in a mystery, behave quite differently from each other.

For more than a century Janeites, a term popularized by Rudyard Kipling, have written full-length novels as homage to their idol. Academics have produced countless papers and numerous books on major and tiny elements of her work, her life, and the Regency period.

Her 250th birthday has brought an even bigger crop than usual, far too many to name. Check your library’s catalog, your bookseller’s shelves, or such online sources as janeaustenbooks.net for whatever you crave after digesting her novels. I’m listing a few recent and new sample titles, ones I’ve read or heard about, to give an idea of the variety available.

Fiction

Longbourn by Jo Baker: Below the stairs in the P&P household.

Jane and the Unpleasantness at Scargrave Manor: Being the First Jane Austen Mystery by Stephanie Barron: Opening a long-running series in which Jane applies her wit to solving crimes.

Death Comes to Pemberley by P. D. James: Trouble on the estate a few years after Elizabeth and Darcy marry.

The Austen Society by Natalie Jenner: A well-researched novel on post-World War II efforts to save Jane Austen’s last home.

Pride, Prejudice, and Other Flavors by Sonali Dev: A modern Pakistani family’s story parallels that of the Bennets.

The Austen Affair by Madeleine Bell: A rom-com with young actors in a movie based on Northanger Abbey accidentally time traveling.

Nonfiction

What Matters in Jane Austen? Twenty Crucial Problems Solved by John Mullan: Answers to many questions for Janeites and those interested in the Regency period.

Wild for Austen: A Rebellious, Subversive, and Untamed Jane by Devoney Looser: A scholar with a nonacademic style portrays Austen’s not-so-quiet life.

Jane Austen and the Creation of Modern Fiction: Six Novels in “a Style Entirely New” by Collins Hemingway: For readers and writers. And professors.

Jane Austen and the Price of Happiness by Ingrid Sigrun Bredkjaer Brodey: All about the (sometimes unsatisfactory or controversial) endings of the six novels from an original thinker.

Jane Austen, Abolitionist: The Loaded History of the Phrase “Pride and Prejudice” by Margie Burns: The use of the phrase before and after Austen and what it meant to her.

What Jane Austen’s Characters Read (and Why) by Susan Allen Ford: What reading choices reveal about the characters in the novels and about their creator.

Jane Austen: The Original Romance Novelist (Pocket Portraits) by Janet Lewis Saidi: Moments in the life of a brilliant, complicated woman that shaped her writing and led to lasting popularity.

The Jane Austen Insult Guide by Emily Reed: Clever takedowns from Jane for your use in uncomfortable situations.

We’re never going to find new Jane Austen novels, but they’re all worth rereading and rereading. Doing so is likely to lead to reading lots of books about her.

—Carolyn Mulford

I Am a River

Each week I lunch with a group of friends and discuss a topic. Last time the coordinator posed this question: What is the shape of your life? The answers included a rectangle, a vase, a cloud, and an octagon. Usually I wing it, but this time I wrote my response.

The Shape of My Life

I am a river,

Birthed in a puddle,

Nourished by rain,

Pushed to overflow

And grow broader

And deeper.

Springs and creeks fed my flow.

Widening waters gathered force,

Thrusting me against unyielding barriers

And cascading me over rocky falls.

Other streams joined my journey,

Enriching my waters,

Sharing my dreams,

Bringing me love and joy,

Allowing me to give.

Now levees restrict my passage,

Compelling my waters to slow

And grow shallow,

Directing me into the desert.

—Carolyn Mulford

Where to Find My Books

While only one of my books, Show Me the Sinister Snowman, continues to be published in print and electronic editions, several of my novels are available from online sellers. Most of the copies are used, but columbiabooksonline.com, my supportive local bookstore, has a small stock of new Show Me hardbacks and paperbacks.

I also have a few copies of all my novels except The Feedsack Dress, my historical children’s book, and Show Me the Murder, the first in my mystery series featuring a former spy returning home and solving crimes with old friends. Fortunately e-editions still exist. Barnes and Noble carries The Feedsack Dress ($2.99), and Amazon offers Show Me theMurder ($3.99).

A search of used-book sites, such as abebooks.com, may turn up copies of all my books—even the nonfiction ones that are so old they must have come from estate sales.

You may still find my novels at your local library or ask it to borrow these for you through the interlibrary loan program.

I’ve no new books to announce, so I hope readers will continue to enjoy the old ones.

—Carolyn Mulford

The Turkey That Bullied Me

I grew up with animals as friends, the first being our dog Roamer. He and I wandered around the yard, the barnyard, and the garden. Roamer barked at squirrels and chased rabbits from our vegetables. He made me ponder one of life’s great puzzles: Is it okay to sympathize with Peter Rabbit in the story but condemn him when your own carrots are at risk?

Roamer knew not to chase our chickens or cows or pigs, and he joined me in playing with an orphaned lamb and the kittens whose parents kept the barn free of mice.

What he didn’t do was defend me when my parents set a new turkey loose by the corncrib at the back of the barnyard. I first encountered the turkey when I went to the two-hole outhouse next door to the corncrib. It peeked out from the back of the corncrib and, head bobbing, ignored my friendly greeting.

Roamer stared at the big bird and casually walked a little closer to the house.

When I came out, the bird didn’t show himself. I took several steps and heard the whishing of flapping wings and saw a turkey as tall as I was rushing after me. I ran, but the turkey had momentum and managed to slap me with its wings before I could pick up speed.

Roamer barked but didn’t advance. Still it was enough to discourage the turkey and allow me to escape. That time. People say turkeys are dumb, but that one quickly learned to rush at me from hiding. It realized it had nothing to fear from me, Roamer, or even my big sister, who was only slightly taller than the turkey.

My father urged us to face the bully, and we armed ourselves with sticks to swing and corncobs to throw. Mostly we just barreled out of the outhouse door and ran like crazy. My sister and I both suffered wing beatings and beak peckings.

Then my mother took action. I don’t remember, but I think my father helped catch the free-range turkey and button an old sweater over its body to hold down its wings. It attempted to attack me any time I invaded its territory, but now I could outrun it.

Then came Thanksgiving, the first one I remember. We ate that mean turkey. It was tough. For years after that we ate an old hen with dumplings and noodles at Thanksgiving.

—Carolyn Mulford

How Editors Stay in Style

If you’re an editor, you know the importance of the new 1192-page 18th edition of the Chicago Manual of Style. Since the University of Chicago Press published the first edition in 1906, other book publishers, many periodicals, and now electronic publications have accepted Chicago as the primary guide.

Even publishers who write their own style manuals, or settle for a pamphlet on which Chicago guidelines they don’t accept, study the latest edition to adjust editorial styles.

Without style manuals, we would rely on writers’ personal preferences and editors’ memories to be consistent on thousands of disputed questions. The two most common may be which numbers to write out and whether to use the serial comma. Most newspaper style manuals, for example, digress from Chicago in writing out numbers up to 10 (versus through one hundred) and in omitting the comma before and in a series (e.g., apples, oranges and bananas) unless it’s required for clarity.

IMHO, whatever the style manual, clarity should supersede consistency.

Chicago’s editors do extensive research and consultation on trends. The 18th, for example, reaffirms some old wavering choices (e.g., capitalizing the first word in a complete sentence following a colon) and identifies spelling preferences for new terms (e.g., omitting the hyphens in ebooks and esports).

Hyphenation is a major headache, and the manual devotes more than a dozen pages to multiple examples of pesky hyphens. Through several editions, I’ve referred to that advice more than any other.

Some changes reflect social attitudes, including preferred ways to refer to individuals or groups. In an earlier edition, editors recommended accepting they as a singular (standard centuries ago then abandoned in formal writing) but withdrew it because of protests. The 18th edition cautiously gives they as an option for referring to a person whose gender is unknown. Stay tuned.

Another change is capitalizing Indigenous, considered a parallel to Black and White. (Some style manuals favor lower case for all three.) In recent decades I‘ve seen editors move from Indian to Native American or the name of a particular tribe (e.g., Navajo) to American Indian.

The 18th also updates production sections, including advice for self-publishers on such basics as choosing fonts and margins and such new problems as preparing notes for an audio book. AI receives attention (e.g., citing AI-generated images).

To read more information on changes in all sections, go to https://www.chicagomanualofstyle.org/help-tools/what-s-new.html. If you want to buy the 18th, shop around for the best price. The list price is $75, but you may find a better deal from the publisher or an online bookseller. If you plan to use the manual in an editorial office or don’t lift weights, consider the online edition.

—Carolyn Mulford

Advice to My Younger Self

What message would you give your younger self?

I didn’t want to answer that question, the topic for conversation at a recent lunch. My naïve teenage self knew little of life beyond my farming community, and the whole world has changed incredibly since then. Specific advice from my work as a writer or my griefs and gratifications as an adult would have meant little to me then.

Reluctantly I dredged up five general observations that might have helped me 70 years ago.

- Life is a learning process. Growth doesn’t stop in our twenties, or even fifties. You never know enough to consider your education complete. Respect the past, live in the present, anticipate the future.

- You will go places and do things you can’t imagine—and not do things you take for granted will be part of your future.

- Don’t let fear stop you from pursuing opportunities in both your professional and your personal life.

- Friends will become as close as family. You will enjoy and value family members more as an adult, but you will share the most with those you choose to embed in your life.

- A life without failure lacks adventure. If you try only those games or jobs or relationships in which you’re sure to succeed, you stunt your growth.

And my advice to myself on my 85th birthday: It ain’t over ’til it’s over.

—Carolyn Mulford

Why we needed Title IX before 1972

The fiftieth anniversary of Title IX, a landmark law requiring gender equality in schools receiving federal funds, reminded me of how little opportunity to play sports most females of my generation had. (Title IX changed much more than sports, but that’s another story.)

In my one-room school with roughly a dozen students in grades one through eight, we had no organized physical education program for girls or boys. We played together at recess and noon, mostly baseball or games involving some form of tag. Our entire sporting equipment consisted of two bats, a softball, a baseball, and a volleyball (used for playing handy-over, with half the school on one side of the coal shed and half on the other).

In ninth grade, as I wrote in The Feedsack Dress, the most familiar sport to country kids—and the least played in girls’ P.E. class—was softball. By the time I learned the basic skills of an exotic game like deck tennis (played much like volleyball but with a hard rubber ring), a new game popped up. I added little to my homeroom’s intramural teams.

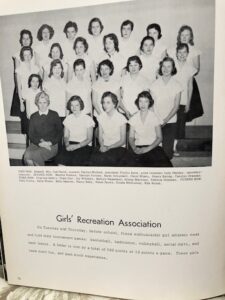

Neither my senior high school nor college in Kirksville, Missouri, fielded girls’ teams that competed with other schools. Neither had a swimming pool, and the high school had no playing field or tennis courts for girls. High school P.E. classes met in the basement gym. There we did boring calisthenics and played deck tennis, aerial darts, badminton, volleyball, and basketball. I was surprised to learn I had lettered my senior year (rare for a girl). I did it by recruiting the school’s best players for my intramural teams. If my memory is accurate, we won all the tournaments. The only mention of girls’ sports in the high school yearbook was the page above, which shows the members of the Girls’ Recreation Association (I’m second from left on the front row).

The college’s program offered little more than the high school did, though I did learn to play table tennis and jump on a trampoline. My athletic high point: The women’s P.E. Department (two women) let me substitute a softball elective for a required calisthenics course. As a grad student at the University of Missouri, I saw no opportunity to participate in any sports. One woman among several men in the renowned journalism school aspired to be a sports writer.

Finally, during Peace Corps training at Georgetown University, I received introductions to swimming, soccer, and cross-country running. My physical education consisted of appetizers but no main course.

The real national awakening to the potential of women’s sports took place in September 1973, more than a year after Title IX, when Billie Jean King took down Bobby Riggs in the Battle of the Sexes. She changed not just tennis but the recognition of women as athletes. She has continued to push for equal pay and power on the court and off ever since.

Even with the much greater (though not equal) opportunities today, I wouldn’t have become a great—even a good—athlete, but several of my classmates could have. And school would all have been more fun.

Equal opportunity, wherever you find it, makes life less frustrating and more rewarding.

—Carolyn Mulford

Concert Jogs Memories of Vienna

Memories interrupted my enjoyment of the Vienna Philharmonic’s New Year’s concert broadcast last night on PBS.

Unlike my Show Me protagonist, a CIA covert operative embedded in Vienna, I lived there only three years, but we shared a love of the city’s music. I went to the opera, an orchestra concert, chamber music, an operetta, or some other musical performance once or twice a week. Tickets were cheap, particularly if you were willing to sit in the balcony directly above a chamber orchestra using the instruments in vogue when the music was composed centuries ago.

You could usually get a late ticket to stand at the back of the Musikverein’s high-ceiling rectangular grand hall, and people were there at last night’s event. I could spot where I stood to hear Leonard Bernstein as a guest conductor.

Every venue has excellent acoustics, and every audience knows the music and expresses approval or disappointment through applause. The Viennese love traditional favorites, including such Strauss compositions as Tales of the Vienna Woods. Even so, the 2022 performance included something I don’t remember hearing before, the musicians augmenting their instruments with singing and whistling at one point. The audience approved.

As usual, the favorite final encore, “The Radetsky March,” elicited an enthusiastic audience response. Everyone clapped without missing a beat.

The music lovers wore masks and the walls gleamed with gold (lacquer?) last night, but the orchestra’s performance and the audience’s appreciation have not changed.

—Carolyn Mulford

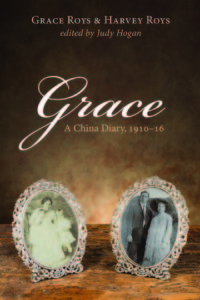

Guest Post: Judy Hogan on Grace: A China Diary, 1910-16

A North Carolina author, teacher, and activist, Judy Hogan has written everything from mysteries to poetry to memoir. (For more about her and her work, visit http://judyhogan.home.mindspring.com.) Even so, editing and annotating her grandparents’ diary evoked emotions her other books didn’t. She tells us why she worked so hard to pull together information on their life in China.

Judy Hogan

Probably the most important event of my life was going to Russia in 1990 as part of a Sister Cities of Durham Russia writer exchange program, and all the experiences that followed from it, with many visits and mutual publishing projects. The second most important event happened in April when my book of and about my grandmother’s diary was published. Here my learning experience was related to China, where my mother was born and her parents were missionaries 100 years ago.

Grace: A China Diary, 1910-16 arrived in my post office Saturday, April 15. We’re a village, and we chat in the post office. I was chatting with a friend I rarely see, and our postmaster, Robin, handed me a priority envelope from my publisher, Wipf and Stock of Eugene, Oregon. I tore it open, and there was a shrink-wrapped package, with a sheet of paper over the cover. “I need scissors,” I said.

Robin provided them, and I got the two paperback books free of the plastic. There it was. I let Robin hold one (she had already said she’d buy it), and a man named Mr. Moon asked if it had pictures in it. I showed him the pictures near the front and said, “That was in China in the early 1900s.” He said he wanted a book, too.

I’d been able to publish 14 books before Grace arrived. Why was it such a big deal? Here’s part of the answer, from the first chapter of Grace.

Finding Grace: By age six one of the most important people in my life was Grace, my maternal grandmother, who, with her husband Harvey Roys, had been a missionary in China. Closely tied to Grace was another Grace, her daughter, born September 1915, who died at age eight in 1924 from heart complications following scarlet fever. Early in 1944 my mother moved my sister and me from Cameron, a small town in West Virginia, where my father, William Robert Stevenson, had been the minister of the Presbyterian Church, and where I had felt loved and protected on all sides, to Norman, Oklahoma. My father had volunteered to go into the Navy as a chaplain and was stationed in McAlister, not far from Norman, where my grandfather and grandmother Roys lived. Grandpa taught physics at the University of Oklahoma there.

Finding Grace: By age six one of the most important people in my life was Grace, my maternal grandmother, who, with her husband Harvey Roys, had been a missionary in China. Closely tied to Grace was another Grace, her daughter, born September 1915, who died at age eight in 1924 from heart complications following scarlet fever. Early in 1944 my mother moved my sister and me from Cameron, a small town in West Virginia, where my father, William Robert Stevenson, had been the minister of the Presbyterian Church, and where I had felt loved and protected on all sides, to Norman, Oklahoma. My father had volunteered to go into the Navy as a chaplain and was stationed in McAlister, not far from Norman, where my grandfather and grandmother Roys lived. Grandpa taught physics at the University of Oklahoma there.

Living with my grandparents at that time was also their younger son, Harvey, who was in medical school. Mother had taken a job with the YWCA on the O.U. campus. There were two naval bases in Norman, and housing was hard to find, so we lived three months in a small house with my grandparents and my uncle.

For the first time in my life I wasn’t happy. My school teacher was harsh, threatening us all with being sent to the principal if we misbehaved. She was said to have a rubber hose with which she beat children. I was missing my father. Uncle Harvey, whom I at first had admired, had little sympathy for a six-year-old. My grandfather was impatient, too, when I complained about the long walk to school—about a mile. He said he’d walked farther than that when a child. Grandmother Grace startled and scared me when I encountered her as she was waking from a nap in the basement room. She told me she had dreamed she had gone to heaven to be with Gracie. She seemed sorry to have awakened.

Mother wasn’t happy either. Her new-doctor brother Harvey told her she should have the lump in her breast removed immediately. Then he heard me complaining about my long school walks and how my legs ached, and he urged Mother to take me to a doctor, as I might have rheumatic fever. The diagnosis was confirmed by the local doctor. Somehow during this time, I identified myself with my mother’s little sister, Gracie. The family myth about Gracie was that she had been angelic. By the time she died, she had found her lord and savior. Gracie went straight to heaven. No one else could compete with her goodness, especially after she died.

By the time Mother found us a very small house to rent in May, conveniently across the street from a different and kinder elementary school, I had been diagnosed with rheumatic fever, and bed rest was ordered. I lived in bed for a year. At first Mother arranged babysitters for me and my little sister, Margaret Elaine, so she could keep her new job, but she quit before long and stayed home with us. Gasoline was rationed, but every now and then Grace and Harvey drove across town to visit us. Grandmother gave us rabbits one Easter. For many mornings after that Mother had to chase them down, as they got out and into the neighbors’ gardens. Finally one died, and she encouraged a little boy who was visiting me to take the other one home. I learned much later she was afraid to get rid of the rabbits openly because they had been her mother’s gift to us. I didn’t know then that Grace had bi-polar disease. This might explain why Mother didn’t want to upset her mother.

***

It’s hard to go back to your early life and take on the ghosts that are still there, and try to put them to rest. Mother was my main source of information about Grace, her mother, who had been unreliable for her, beginning at age 12, when she had to be hospitalized. She described her mother as “brilliant, high-strung, highly sexed, artistic, and crazy,” and without her ever saying this aloud, my sister and I felt like we were being watched for the craziness to come out. We were talented, she in music, I in writing, and we had a normal interest in sexuality. We were smart, but probably not brilliant. I had a line in my head which I sometimes quoted in newspaper interviews: “If I didn’t write, I’d go crazy.” I eventually learned in therapy that I had unconsciously identified both with Grace and her daughter, Gracie.

Mother gave me a lot of family papers, including the diary that Grace and her husband Harvey had kept in the early years of their marriage, 1910-16, and in 2004 I decided to annotate it and try to publish it. I had friends make suggestions, and I researched China, even though I had taken a dislike to China in early childhood when Mother explained that the Chinese devalued girls and sometimes put them to death. Research isn’t my favorite writer thing to do. I like to write from my own experiences and imagination, but something urged me to understand Grace, even if it meant dealing with China. I had helpers all along the way, and gradually got past my negative feelings about China and came to love Grace.

Only toward the end did I stumble on the fact that Grace’s mental illness probably got worse because her first 32 years had been spent in China, with those wise, loving servants, and in the missionary community which was also loving and supportive, and in Oklahoma where they ended up, she had one college girl living in to help her, and she had three school-age children to cope with, and no supportive community. She spent most of the rest of her life in Oklahoma’s Central State Mental Hospital.

I think I was wanting to redeem her, be the artist she had failed to be. It hit me a few days ago that she was Henry James’s “failed artist,” the perfect character for a novel. The book is all true, but it has the story of Grace, mostly in her own words in the diary. In those years she was happy, loved her babies, was an important member of the Nanking missionary society, played organ and piano, led children in Christmas music, went on little jaunts with Harvey, as well as hunting and chasing wild pigs on horseback. So Grace is out there now, and people are buying it, more than I expected, and its being out there comforts me.

***

Here’s the key info: Grace Woodbridge Roys suffered from bi-polar disease before it was well understood. Her daughter feared that her children would also suffer mental illness. This annotation of Grace’s diary opens the early 1900s missionary world in China and the personality of Grace to the reader. In December 1910 Grace married Harvey Curtis Roys, who was teaching physics at Kiang Nan government school in Nanking, under the sponsorship of the YMCA. Grace had had a mental breakdown weeks earlier when her missionary father forbade the marriage.

The diary records their early married life, the births of their first two children, their social life with other missionaries in China, many of whom made major contributions to Nanking life and education: medical doctors and nurses; theology professors; agricultural innovators; founders of universities, hospitals, nursing schools, and schools for young Chinese women and men. Included is their experience evacuating during the Sun Yat-sen Revolution of 1911. Well-known missionaries of that time came to tea and taught at the Hillcrest School the mothers began for foreign children. The Nanyang Exposition took place in 1910, too, as China was in the throes of entering the modern era, with trains, electricity, telegraph, and a new interest in democracy.

***

Comments from Experts: “This thoroughly annotated five-year diary, including contemporary accounts of the retreat colony Kuling and schools in Nanking, provides rich and illuminating primary documentation toward understanding the daily personal, family, social and professional lives of American educators and missionaries in early 20th century China, the native culture in which they devoted themselves, and their influence on subsequent generations. A graceful window on the lives of Westerners and Chinese alike.” J. Samuel Hammond, Duke University.

“Grace, a rich portrait of missionary life in early 20th century China, is told through diary entries, photos, narratives, and an epilogue by Judy Hogan, editor and annotator of her grandmother’s diary. Most poignant for me, as a former missionary child, is Hogan’s appreciation of Grace’s difficult transition from the China where she spent her first 32 years to the United States where her mental illness took flight.”–Nancy Henderson-James, author of Home Abroad: An American Girl in Africa

Grace: A China Diary, 1910-16, edited and annotated by Judy Hogan. Authors: Grace and Harvey Roys. Wipf and Stock, Eugene, Oregon. ISBN: 978-1-5326-0939-8. Paperback: $26; Kindle, $9.99. Independent bookstores may order from Ingram or www.wipfandstock.com. For signed books, send order ($30 including tax and postage) to Judy Hogan, PO Box 253, Moncure, NC 27559.

My Interview on Postmenopausal Zest

Today my answers to Judy Hogan’s questions about my writing, particularly the Show Me series, appear at http://postmenopausalzest.blogspot.com.

She asked what prompted my switch from nonfiction to fiction, why I created the series, how the original idea fared over five books, and what prompted me to mix cynicism and compassion in Phoenix Smith.

And, of course, she wants to know more about Achilles.

—Carolyn Mulford

Coming: Show Me the Sinister Snowman

Cave Hollow Press has completed the cover design, the penultimate step in publishing Show Me the Sinister Snowman. The fifth book in the series will go to press (and to digitalization) for release March 31.

Coming March 31, 2017

The first book, Show Me the Murder, takes place in May. Former CIA covert operative Phoenix Smith returns to her Missouri hometown to recover from being shot. Phoenix works with an old friend, Acting Sheriff Annalynn Carr Keyser, to learn the truth about her late husband’s violent death. Phoenix rescues a wounded witness, a Belgian Malinois named Achilles. A K-9 dropout, he becomes her valued sidekick. To Phoenix’s annoyance, struggling singer Connie Diamante insists on taking part in this and subsequent investigations: in June, Show Me the Deadly Deer; in August, Show Me the Gold; in September, Show Me the Ashes.

In book 5, it’s the week before Thanksgiving. Annalynn has completed her term as sheriff and is campaigning to replace a congressman who died in an “accident.” Phoenix, a certified capitalist, is stuck running the foundation she established to give Annalynn a job. The ex-spy is bored until a woman hiding from an abusive husband begs the foundation to protect her.

Phoenix and friends accompany Annalynn to a political gathering in an isolated antebellum mansion. A blizzard traps them there with a machete-wielding man lurking outside and an unidentified killer inside.

—Carolyn Mulford

Marching in the 1993 Inaugural Parade

Today’s presidential inauguration reminded me of the good and bad in taking part in the inaugural parade 24 years ago.

As the 1992 presidential campaign wound down, the Washington, D.C., chapter of Returned Peace Corps Volunteers asked if members would like to march in the inaugural parade.

Like most locals, I avoided going near the Mall when the crowds came to town, but I couldn’t resist the chance to take part in this national event. Neither could Joyce Campbell, another RPCV from the 275-strong Ethiopia I group. We signed on.

We waited weeks to hear whether an RPCV with political connections could convince the parade organizers to allow us to publicize the Peace Corps. Twenty-two years after its founding, some 150,000 had served, but many people had forgotten about this one-to-one foreign aid program. (Today more than 7,000 PCVS are serving, and 225,000 RPCVs have served in 141 countries.)

The parade was to begin at 2 p.m. At 8:30 a.m., Joyce and I met to ride the Metro from Silver Spring, Maryland, through D.C. into Arlington, Virginia. We met our group—about 100 RPCVs who had served in 50 or so countries—in the enormous Pentagon parking lot.

After learning our assigned positions, we boarded buses and rode to our waiting spot on the Mall near the Museum of American History (at least a half mile from the Capitol). The buses dropped us off around 10:30, leaving us to mill around with no place to sit.

The temperature was near freezing, and the sun shone halfheartedly. Having worn a heavy sweater beneath a super-warm coat and warm hiking socks under snow boots, I stayed warm as long as I kept moving.

At noon, speakers broadcast the inauguration ceremony and, memorably, Maya Angelou reading her poem. Then the new president and Congress had lunch in the Capitol. We ate box lunches in the cold.

We didn’t line up with our flags until well after 2, and we didn’t move for another hour. Instead of going all the way to the Capitol, we cut left to Pennsylvania Avenue around 4th Street. The crowd had thinned out by then (coming up on 4 p.m.).

Joyce, a later Ethiopia RPCV, and I took turns carrying the heavy, long-poled Ethiopian flag. A nearby band gave a beat to march to as, adrenalin flowing, we moved at an irregular pace up Pennsylvania toward the White House.

With the sun dimming, we turned onto the last block and saw nearly empty bleachers across from the president’s viewing stand. He’d delegated greeting the marchers to the vice president. Al Gore, the only one in the viewing stand focused on the parade, gave us a big thumbs up.

Our group broke up right after we passed Blair House. We turned in the flag at the waiting bus and headed for the nearest Metro stop.

Like the Peace Corps, the inaugural parade had been tiring and taxing, but being part of the Peace Corps for two years and of a historic transition for one day had been well worth it.

—Carolyn Mulford