When The Feedsack Dress came out in 2007, I started a blog on Typepad that focused on life during the late 1940s and early 1950s. I stopped posting there in 2012, but you can still link to The Feedsack Kids. I’m posting some new blogs and my favorite old ones here.

Category Archives: Writing

Creating a Canine Character

To help a friend worrying about “interviewing” pets for a community newsletter, I dug up my old guest blog for Wicked Cozy Writers on portraying a dog as a supporting character. Here’s an adaptation.

Planning Show Me the Murder, I spent weeks envisioning three old friends reunited in their hometown: Phoenix, a wounded former CIA operative; Annalynn, a do-gooder whose husband died in a sleazy motel; and Connie, a struggling singer/music teacher.

Mid book, a Belgian Malinois named Achilles popped up as a plot point—the only witness to a crime. Phoenix finds him shot, starved, and tied to a tree. She identifies with him, saying, “Some of us don’t die so easily.” They adopt each other.

Achilles posed some special challenges. One was revealing his personality and ability when he couldn’t talk and arrived with no backstory. What he couldn’t tell, he had to show. For example, when Phoenix left him alone initially, he howled until she came back. When she took him into the backyard, he protected the hummingbirds from cats skulking at the feeders. When he met Connie, he offered a paw for her to shake.

In each book, he—like the women—revealed more of himself. For example, in Show Me the Deadly Deer, he refused to get out of the car when rambunctious four-year-old twins wanted to play with him. After the children faced a tragedy, he allowed them to maul him with affection. In Show Me the Gold, he even criticized his adored Phoenix, barking a reproof when she raised her voice to Annalynn.

A persistent problem was depicting the omnipresent dog’s actions. I constantly asked myself where he was. Is he glued to Phoenix’s leg (danger close by), sniffing to read the scene (curious and careful), standing by the car to say he wants to go home (bored)? What’s more, his actions had to contribute to plot and/or character.

His nose, intelligence, and personal qualities contributed to every investigation. In Deadly Deer, he indicated that the murder didn’t take place where they found the body. In Gold, he warned Phoenix of a booby trap. She also learned to use him to disarm innocents, terrify bad guys, and back her up. He offered another unanticipated advantage: He exposed the softer side of the tough, cynical Phoenix.

Achilles became crucial to my fictional world. At every book signing, someone said, “I love your dog.” So did I, but I never got over readers praising my canine character more than my human ones.

—Carolyn Mulford

Looking Forward 60 Years Ago

Reminders of my attempts to start my writing career arrived last Christmas. A friend, Joyce Campbell, sent me letters I had written to her while we were serving as Peace Corps Volunteers (teaching English) in Ethiopia from September 1962 to July 1964 and in the months after we returned home (Chattanooga, Tennessee, for her and Kirksville, Missouri, for me) after traveling through Europe.

On December 21, 1964, I wrote, “Has anything turned up for you yet? People don’t seem terribly impressed with Peace Corps experience for job qualifications it seems to me. I’m going down to the University Placement Bureau [University of Missouri School of Journalism] after New Year’s, I guess, and see what pedestrian ‘good experience’ job they can turn up. I may go to N.Y. and go down magazine row if nothing shows up fairly soon, but I think jobhunting will be pretty futile until I’ve had some journalistic experience—big frog in little pond first. Are you considering teaching again?”

On January 5, 1965, I replied to her letter expressing distress about the open racism all around her, and common in my town. I suggested she go elsewhere for grad school. I also reported on friends seeking jobs in D.C.: “A friend said agencies are getting a little tired of all the ex P.C. applicants.”

On January 24, I wrote about giving talks on my Peace Corps experience, attempting to write a short story, and reading books on writing fiction. I’d applied, without success, for a job in Hallmark’s public relations department in Kansas City and turned down a job teaching journalism and freshman comp at Northeast Missouri State Teachers College, where I’d earned my B.A. and B.S. in Education.

I was determined to stay in journalism. “It occurred me that a possibility for both of us is McGraw-Hill. They are working on a lot of textbooks for overseas markets. I’m not particularly hep on that, but they also publish a number of trade magazines.”

We agreed that that we shouldn’t rush decisions. “I keep thinking that never again will I have free time and free board & should let jobhunting take its course and try to do some real writing.”

A month later I expressed my frustration with my attempts at writing articles on the P.C. experience and a short story. (I wouldn’t have a short story published until the 21st century.) I have absolutely no memory of this story, but below is my description. It reflects the language and attitudes of the time and my accurate appraisal of my skills.

“The short story is about a teacher told to make sure her Negro pupils have prominent parts in the Christmas program so that everyone can see how liberal the school is. She gets in trouble when she has a Negro Joseph and a white Mary. The theme of the story as it stands now is really the necessity of compromise and gradual progress. The solution is weak because it is a happy coincidence instead of an actual solving of a dilemma, but this is also a theme in that sometimes there is no solution.”

Later in the letter, I responded to one of her comments. “You said idealism is out of style. I think a lot of people are theoretically idealistic. They are the ones who think we have done a wonderful thing [serving in the Peace Corps] and may even imagine themselves doing it for a couple of minutes.”

My last letter in the series was dated March 18, 1965. I congratulated her on finding a job. (Soon she joined a special grad program on teaching in disadvantaged neighborhoods in Cleveland.) I had sent 10 letters to selected magazines and was planning a trip to D.C., where I could stay with a good friend from college, while seeking a job in person.

In May 1965, the combination of letters and appearing in person netted me an editorial job at the NEA Journal, then a top monthly published by the National Education Association. My Peace Corps teaching experience proved a plus, and it didn’t hurt that the renowned editor, Mildred Sandison Fenner, came from northwest Missouri.

This wonderful first job taught me an immense amount about writing, editing, and organizing a magazine. I was on my way.

Carolyn Mulford

How Editors Stay in Style

If you’re an editor, you know the importance of the new 1192-page 18th edition of the Chicago Manual of Style. Since the University of Chicago Press published the first edition in 1906, other book publishers, many periodicals, and now electronic publications have accepted Chicago as the primary guide.

Even publishers who write their own style manuals, or settle for a pamphlet on which Chicago guidelines they don’t accept, study the latest edition to adjust editorial styles.

Without style manuals, we would rely on writers’ personal preferences and editors’ memories to be consistent on thousands of disputed questions. The two most common may be which numbers to write out and whether to use the serial comma. Most newspaper style manuals, for example, digress from Chicago in writing out numbers up to 10 (versus through one hundred) and in omitting the comma before and in a series (e.g., apples, oranges and bananas) unless it’s required for clarity.

IMHO, whatever the style manual, clarity should supersede consistency.

Chicago’s editors do extensive research and consultation on trends. The 18th, for example, reaffirms some old wavering choices (e.g., capitalizing the first word in a complete sentence following a colon) and identifies spelling preferences for new terms (e.g., omitting the hyphens in ebooks and esports).

Hyphenation is a major headache, and the manual devotes more than a dozen pages to multiple examples of pesky hyphens. Through several editions, I’ve referred to that advice more than any other.

Some changes reflect social attitudes, including preferred ways to refer to individuals or groups. In an earlier edition, editors recommended accepting they as a singular (standard centuries ago then abandoned in formal writing) but withdrew it because of protests. The 18th edition cautiously gives they as an option for referring to a person whose gender is unknown. Stay tuned.

Another change is capitalizing Indigenous, considered a parallel to Black and White. (Some style manuals favor lower case for all three.) In recent decades I‘ve seen editors move from Indian to Native American or the name of a particular tribe (e.g., Navajo) to American Indian.

The 18th also updates production sections, including advice for self-publishers on such basics as choosing fonts and margins and such new problems as preparing notes for an audio book. AI receives attention (e.g., citing AI-generated images).

To read more information on changes in all sections, go to https://www.chicagomanualofstyle.org/help-tools/what-s-new.html. If you want to buy the 18th, shop around for the best price. The list price is $75, but you may find a better deal from the publisher or an online bookseller. If you plan to use the manual in an editorial office or don’t lift weights, consider the online edition.

—Carolyn Mulford

In Praise of “Said”

When I began the transition from nonfiction to fiction, writing dialogue seemed easy. Then my critique readers pointed out my lack of skill in using tags, the words that identify the speaker. In general, tags precede (Mary said, “You’re late. Get going.”), lie within, (“You’re late,” Mary said. “Get going.”), or follow the dialogue (“You’re late. Get going,” Mary said.).

Even if only two people are talking, readers need reminders of which one’s speaking after a few exchanges. The writer fails if the reader has to go back to figure out who’s saying what. Rule of thumb: When the reader pauses, the writer loses.

If the dialogue stands strong, the reader may need only a quick, direct ID. The top choice is the speaker’s name (or a stand-in for it) and said. At first I doubted this, thinking that verb too common and dull. Later I realized that much of the value of said comes from its being inobtrusive and neutral.

Guard against replacing “said” with a vocalization—e.g., shouted, screamed, muttered, murmured, hissed, growled—that doesn’t fit the situation just because you seek a synonym. I may run a search to catch an overuse of any of those words. In an entire novel, you may need to rewrite if anyone mutters or shouts more than five or six times. An exception would be using some manner of speaking, such as murmuring, to portray a character.

Writers often turn to asked and exclaimed for variety. Fine, but be careful. As an editor, I object to the redundancy of asked plus a question mark and exclaimed plus an exclamation point. For example, Mary asked, “What did he want?”

Another handy tag is the listener’s name in the dialogue, as in, “John, you know I’ll never agree to that.” Limit that ploy to two times in an exchange.

Tags often serve as much more than IDs. They can reveal character, show action, and emphasize setting. Instead of Mary said, tell the reader what Mary did or how, when, where, or why she did it. For example, Mary stood on tiptoe to peer over the stone wall. “The bedroom light’s on, but I don’t see anyone.”

Another function is to clarify what the reader can’t determine from the words on the page. If the character says, “I’d never do that,” is he being sarcastic or earnest or deceitful? Sometimes the most efficient way to convey that is through the scorned adverb, e.g., said hotly.

Partly to avoid adverbs, we lean on a dozen or so handy verbs, such as smile, grin, laugh, giggle, and chortle. When is the last time you chortled? In my drafts, I search for a surplus of such verbs and phrases, including nod, shrug, raise an eyebrow, glance, study, stare, turn away, lean back/forward. Know thyself and search accordingly.

Tags become critical in the difficult scenes with several speakers. Such scenes present multiple technical challenges: differentiating the speakers, establishing their physical positions in relation to each other, and focusing on plot amidst multiple reactions. Sometimes writers block out crowded scenes the way a stage director would before writing them.

A common place for such scenes is around a table. Readers soon tune out if the characters do nothing but sip, stir, chew, bite, and gobble. Work to come up with multipurpose tags that emphasize character or advance plot. For example, John cut his pancake into precise one-inch squares. “The medical examiner didn’t find any breakfast in the stomach.”

If you get stuck, fall back on said, at least in the first draft. Most of the time that short, efficient word does the job.

—Carolyn Mulford

Why I Write Short Stories

For years I wrote and edited commercial newsletters. I got tired of the short form, limited content, and demands for accuracy and objectivity. So in my early sixties I revived my dormant goal of writing novels.

Switching from nonfiction to fiction and from 600 to 90,000 words forced me to learn new skills, activate a different part of my brain, and face the financial reality that fiction doesn’t pay well or soon. For the next 10 years, as I served my fiction apprenticeship, my earnings came almost exclusively from my freelance editorial work.

In spare hours, I concentrated on learning to write mysteries. I struggled with pacing and planting clues, but I loved having 30 or so chapters in which to develop characters and explore situations. I had no desire to write short stories.

Then I needed a fiction credit to cite in the query letter to sell my first mystery. The Chesapeake chapter of Sisters in Crime announced open submissions for a short story anthology. If I could come up with a good short story, I could claim status as a mystery writer.

Easier said than done. The short story is a demanding form. In roughly 3,000 words you have to profile at least one compelling character, intrigue with plot, enhance action with setting, and end with a surprising but believable twist. To me, doing all this all depends on having a good idea, one that’s a gold nugget rather than a gold mine.

The best short story writers, including one of my early critique partners, think and write this way. I don’t, but a debate with my critique group on the reality of courage during crisis prompted me to create a notably timid woman. Circumstances force her to outwit and disarm a dangerous man to save her daughter’s life. The story worked, and I became a published mystery writer.

Another practical reason for writing short stories: They can help keep your name before fans and introduce you to others between novels, which generally come out about a year apart. I managed, with difficulty, to write a few short stories for other anthologies between my novels.

I’m not sure these helped my small career, but they challenged me to accomplish a lot in a few words. I rewrote and rewrote and rewrote. As in poetry, every word must contribute to the whole.

The stories for anthologies also gave me a way to test characters and settings that I might carry over into novels. I just read an old story that I had considered turning into a mystery series. Then my Show Me series took off, and I forgot about the other idea.

I still like it. I’m considering returning to the main characters and the setting, but this time for a series of linked short stories. These days writing 3,000 rather than 90,000 words appeals to me.

—Carolyn Mulford

An Aging Writer’s Resolutions

In my early sixties, I resolved to phase out my career as a freelance writer/editor and ease into semi-retirement as a novelist. As a first step, I took a course on writing mysteries. I followed up by forming a critique group with other aspiring writers and writing, at night, a chapter a week.

I finished the first draft of my mystery in about a year. I learned a tremendous amount and became comfortable writing fiction, which requires a different mindset than nonfiction. I couldn’t sell the manuscript even after revision, but writers learn to withstand rejection. I resolved to devote two hours a night to writing fiction.

By age 68 I had sold a novel and a short story and was balancing my time between fiction and nonfiction. By 75 I’d stopped working for clients and spent most of my time writing and promoting my Show Me mystery series. My fiction earnings didn’t compare with those from nonfiction, but that didn’t matter. Much.

My series came to a natural end with Show Me the Sinister Snowman. Holding the details of a mystery’s convoluted plot in my brain was becoming a challenge. I resolved to switch to shorter forms and to increase leisure activities, including the reading I’d sacrificed while writing.

In late 2018, cancer made me doubt whether I’d turn 80. As the New Year began, medication-induced insomnia and energy prompted me to concoct the characters, setting, and plot of a new novel. The concept united a leisure interest, Jane Austen’s novels, and a long-time concern, the survival of family farms. My three pages of notes became a lifeline, enabling me to focus on creating and peopling a world rather than on worrying about leaving mine.

My two critique partners supported my faltering efforts, giving me useful feedback in gentle tones. Chemo cripples the brain for months, and words crawled rather than flowed. Still, by the end of the year I’d accomplished enough to resolve to continue.

Since then I’ve finished several drafts, but not the last. That’s partly because real events affected my made-up ones, largely because I wasn’t satisfied with the result. The book I dreamed of writing remains beyond my capabilities. I can no more be Austenesque than I can run a marathon. I accept that. Also, moving interrupted my final edit in 2023. And, to be truthful, writing took more time and energy than I could muster.

So now what? At 84, writing still gives me a rush. In 2024 I resolve to finish my last novel, a couple of short stories, and a dozen blogs.

—Carolyn Mulford

Preparing for NaNoWriMo

National Novel Writing Month, November, helps writers resist endless rewriting by supporting them in a mad rush to write 50,000 words, more than half the length of most novels. The majority of participants around the world fall short of the word count, but producing even a few thousand words may help a writer develop the habit of writing.

Last week I gave a NaNoWriMo group some tips on getting off to a fast start on November 1.

One of the best ways I know to write fast is to pre-write, to think about what you’re going to write before you face the blank screen. That works before you begin the first chapter and each day thereafter.

How much you plan any novel’s major elements— characters, plot, setting—before you write depends on whether you’re primarily a planner or a pantser. The extreme planners prepare long outlines, extensive character sketches, and detailed setting descriptions. Extreme pantsers start writing with a fragment—an image, a bit of dialog, a personality quirk. Most of us fall somewhere between those extremes. We have to find our own balance.

People plan in various ways. I don’t know of anyone who uses those Roman numeral outlines I learned in grade school. Some common ways: write a short or long synopsis, make a storyboard with sticky notes, put major plot points on a spreadsheet, write stream-of-consciousness notes on the theme or the plot, go through the 12-step hero’s journey.

I tend to let characters and plot simmer over weeks while I’m working on other things. As the idea comes to a boil, I sketch and name characters and draft a 300- to 400-word summary that specifies where the story starts, anticipates high points in the middle, and roughs out of the ending. I make brief notes on upcoming scenes as I write.

Characters drive every novel, and creating the main characters (three to six generally) takes time. So do the peripheral characters (a half dozen to dozen generally), but most can wait. You need to know a lot about the most important character, the protagonist, from the beginning.

For one thing, usually the protagonist is the narrator, either speaking in first person or in a tight third, meaning the reader sees what’s happening through that person’s eyes. If possible, choose your point of view before you write. If needed, change that point of view.

So how do you get to know your protagonist and other characters? You can find suggestions online for writing character profiles or forms to fill out that cover appearance, character traits, etc. The form works fine for minor characters. It also gives you an easily accessed record of such forgettable information as age and hair color.

Some writers collect and paste up photos of people who look like their characters and of the places where they live or go.

At a minimum, decide the traits that govern the main characters’ behavior and determine the role they play in the plot. Your characters direct your plot by how they respond to whatever is happening. And the plot often directs changes in characters’ behavior.

If you don’t already know a lot about your character, ask some simple questions.Introverted or extroverted? Empathetic or mean? Selfish or generous? Loyal or opportunistic? How do the other characters—the sidekick, the love interest, the antagonist—relate to the protagonist?

Remember that almost no one is all good or all bad.

For the protagonist particularly, you need to know the flawsas well as the strengths. What goal or fear is driving that person? What internal conflicts guide their actions in external conflicts?

Learn whatever you need to know to see that person walk into a room, hear them speak, understand how they react in social situations and in a crisis. As you write, you’ll learn more and more about your protagonist—much of which will never appear on the page.

I enjoy creating characters. I like writing a series because in each book you peel back more of the onion and nourish change in ongoing characters. Some writers get their kicks by turning people they know into characters. A lot of mystery writers kill off former bosses.

Naming your characters can take a surprisingly long time, so name as many as you can before you start writing. For me, naming the main characters is very important. The name makes them real, tells me who they are.

I thought a long time before naming the three women in my Show Me mystery series. The protagonist is a former CIA agent who almost dies during a special mission and has to return to her hometown. I called her Phoenix because she has to rise from the ashes of her old life. Also, Phoenix is a distinctive name, one readers remember.

You can look at books of baby names for ideas and original meanings, and you can go online to find the most popular names in the year your character was born. I watch names at the end of movies and TV shows for interesting ones, particularly last names.

One reason naming characters takes time is that you have to make the names distinctive so your readers can tell them apart. Have the names begin with different letters and vary the numbers of syllables. I usually have one character with a two-word name, one known by initials, and one by a nickname.

The other big element is plot. When you’re trying to complete half a book in a month, you need at least a vague idea of the beginning, the middle, and the end. At an absolute minimum know the precipitating incident—where the story starts and why. Otherwise you’ll waste a lot of wondering what comes next. A common error is putting too much backstory and description in the first chapter.

Setting, and I’d include time in this, is usually fairly simple to plan broadly. In some books, setting is insignificant background. In others, it functions as a character. Will you use a real place or one you make up? Will you need to do research? Study maps, walk the area, read its history.

Research can be a major time consumer. Just because you’re writing fiction doesn’t mean you don’t have to get your facts right. Readers know everything.

The amount of research for a book varies widely. Historical novels are research heavy. I spent maybe a fourth of my time over four months studying the New Madrid earthquakes, the region, and concurrent history and culture before I came up with plot and characters. I spent not quite half my time over four months writing and editing Thunder Beneath My Feet. While I was writing, I often had to take time to find a specific fact, such as what songs people were singing in 1811.

If you’re stuck on a detail, note what’s missing and move on. That applies to other things. You can do use Jane Doe or Elmer Fudd for a minor character’s name, give only the vaguest description of a room or street. You may even want to write a one-paragraph summary of a difficult scene and move on to one that’s clearer in your head. Or write only the dialogue. Or write only the action Just note what’s missing.

You have to keep going. One of the purposes of the month is to make you write fast without editing yourself. You’re going to have months to cut all that verbal garbage, insert what’s needed, and polish your language.

What’s you’re going to be writing is a rough draft. You’re also developing the habit of writing. Concentrate on those and worry about the other things later.

—Carolyn Mulford

Work Plan Progress Report

At New Year’s I posted my work plan for 2018 and promised a progress report on my manuscript about a murder at a storytelling festival in North Carolina.

My main characters in Caught by a Tale are a freelancer breaking into true crime reporting and her mother, a retired history teacher and aspiring storyteller.

I chose the setting because I love these festivals, but writing about one has presented some tough technical problems, including making each of the tellers and their stories distinctive without slowing the narrative.

I’m rewriting fairly heavily as I go, and I anticipate spending more time than usual on my second draft. Even so, I’m roughly two-thirds of the way through and expect to finish the first draft in about two months. Right on schedule.

The next two drafts may take a little longer than I thought.

—Carolyn Mulford

Vacationing with Jane Austen

I first read Pride and Prejudice in ninth grade. I didn’t understand it, and her humor went right by me. I read it again in an English Lit class in college and loved it.

Every few years I reread P&P, delighting in Jane Austen’s wry wit. I also have read her other five novels at least once, most of them fifteen years ago as I was planning a trip to England. I particularly enjoyed visiting Austen-related places in Bath and her last home in Chawton, where the small table at which she worked still sits by the window.

Last year I joined the local branch of the Jane Austen Society. A member heard me speak on character development in my Show Me mystery series and suggested I talk to the group about Austen’s characters. I hesitated because I lacked the time and the expertise to address this knowledgeable group, but getting to know Austen better appealed to me. I wondered if offering a novelist’s view of the great writer’s protagonists might be worthwhile.

I decided to take a mental vacation, a journey through JA’s six novels, to indulge myself and to figure out what to say. My itinerary took me from book to book in the order in which she wrote her first drafts: Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice, Northanger Abbey, Mansfield Park, Emma, Persuasion. This allowed me to observe her literary growth from age nineteen to forty-one.

Along the way, I looked for an answer to a fundamental question: Why do the six novels of a writer who died 200 years ago continue to fascinate readers?

My previous readings had produced certain assumptions, not all of them correct.

- The books remain popular because of the characters and the wit, humor, irony, and insight with JA which presents them. The characters are universal and timeless.

- Each book has the same basic cast of characters.*A young female protagonist with a difficult family but one sympathetic sister or friend and a desire to marry for love in a time when economics often determined marriage;

* A wealthy, haughty man who turns out to have a good heart, e.g. Darcy;

* A charming, handsome man who turns out to be a charlatan, e.g., Wickham (characters likes Darcy and Wickham have become a convention in most romance novels);

* An older woman who provides comic relief;

* A man who’s a bit of a fool.

* Enough family, friends, and acquaintances to have a ball.

- Plots always feature a woman without money being pressured to marry for her own and her family’s security.

- The major settings are a village and Bath.

The books differ from each other much more than I remembered. JA never wrote the same book twice.

1 Each protagonist has a distinctive personality. They aren’t just weak versions of P&P’s Elizabeth Bennet and Fitzwilliam Darcy.Each book has at least one interesting female antagonist, some of them fascinating.

- Secondary characters play similar functions in each book but are distinctive personalities.

- The plots are quite intricate. JA lays out clues of what’s to come with the care and subtlety of a mystery writer. (Perhaps that’s one reason so many mystery writers adore her.)

- The settings also have more variety than I recalled. Austen clearly disliked Bath.

Jane Austen considered villages the ideal setting, a place one where everyone knew everyone and all the residents interacted with one another. All of her books have an ensemble cast, but Austen develops some characters more fully than others.

For this journey, I intended to focus on the protagonists and how these women differ. That proved difficult. Often the villagers, particularly the antagonists, demanded equal time.

Sense and Sensibility

Jane Austen started work on Elinor and Marianne in 1795, revised it in 1797, and revised it for the last time in 1810 for publication as Sense and Sensibility. It was her first grown-up novel, one she hoped to get published rather than merely share with family and friends. In her early teens, she’d written largely to amuse, but in S&S she discussed an intellectual issue, the comparative values of sense (basically practicality and rationality) and of sensibilities (basically emotions and aesthetics). The arguments play out in the characters’ actions and reactions, in the descriptions of landscapes, and in various discussions. The theme of sense and sensibility is emphasized much more than the theme of pride and prejudice.

Two sisters are the main characters, but they aren’t Jane and her adored older sister Cassandra. Protagonist Elinor Dashwood, who is 19 going on 30, represents sense and her sister Marianne, who is 17 going on 15, represents sensibility. Sense crosses the finish line far ahead of sensibility. Over the book, both sisters change, but cautious, self-righteous, admirable Elinor modifies her thinking far less than emotional, go-for-the-gusto, pleasing Marianne does.

We know from letters, etc. that Jane hated affectation, particularly people going into raptures over music, art, or scenic views, all of which she loved. That certainly comes across in this book.

Austen’s plots grow from the characters, and the plots reveal those characters. In the best scenes, those revelations come in marvelous dialogue, including long speeches few writers could get past an editor today. Austen also does a lot of telling rather than showing, usually in the omniscient voice, and that’s truer in S&S than her other books.

Here’s a quick reminder of the S&S plot and major players. When Mr. Dashwood dies, John, his son and heir—at his wife Fanny’s urging—sends the second Mrs. Dashwood and his three stepsisters off to live in poverty. Fanny is motivated by money and the threat posed by her brother Edward’s love for Elinor. The book starts slowly with this backstory, but the early dialogue in which John and Fanny justify giving less and less to his half-sisters is hilarious and brilliant in revealing their character. Their little scene hooks the reader.

Mrs. Dashwood’s wealthy relative gives the refugees a cottage and friendship. Elinor tries in vain to keep her mother from overspending and Marianne from dismissing people she doesn’t value. Marianne declares stoic Colonel Brandon, 35, as too old to marry and falls in love with a handsome, charming, young man named Willoughby who spends beyond his means.

Variations of Willoughby appear in all the novels. He spends a lot of time with Marianne and the family, and she gives everyone the impression they’re engaged. He leaves for London and doesn’t write or return. Elinor is the only one not surprised.

The sisters go to London with Mrs. Jennings, a sociable widow of a rich tradesman, although Marianne looks down on her. Initially Mrs. Jennings serves as the comic relief character, but she develops into one of the book’s most admirable people. In London, Marianne learns Willoughby has married for money and makes herself ill—as she thinks a person of sensibility should—by not eating or sleeping. She’s extremely self-centered (she’s 17) and inconsiderate.

In contrast, Elinor hides the pain she’s suffering from a similar loss and remains courteous despite all provocations. She’s astounded when Lucy Steele, a rather desperate young woman who lives by sponging on relatives and friends, reveals she and Elinor’s Edward have been secretly engaged for four years. (JA slips in women’s lack of power and the need to survive by their wits in each book.) The verbal sparring between Elinor and Lucy shows how intelligent both are and what self-discipline Elinor has. Their exchanges are the highlight of the book for me. Edward comes on stage, but we see little of him in the book.

Elinor and Marianne start home, but Marianne becomes very ill and they stay at a friend’s home. Colonel Brandon rides off in a storm to bring their mother. In a major surprise and one of the best scenes in the book, Willoughby shows up to explain why he couldn’t marry the woman he loved. That scene makes him one of the best-drawn of JA’s male characters.

I suspect that a publisher refusing to look at S&S in the early 1800s was a good thing, that JA’s later revisions made it a much better book.

Pride and Prejudice

Austen wrote the first drafts of First Impressions in 1796-97, when she was 20 and 21, and spent some time revising what became Pride and Prejudice after she sold S&S in 1810. One thing writers learn is that the title makes a difference in sales, and the change was important. During her lifetime, her name never appeared on her novels. They were “by a lady.” The parallelism of Sense and Sensibility and Pride and Prejudice helped link the books in the minds of readers and encourage sales.

Reading S&S and P&P back to back showed me Austen made a great leap forward as a writer. In terms of structure, characterization, and wit, P&P is a much stronger book than S&S. The second book is superbly crafted. The opening chapter grabs you and propels you into the story. JA does much more showing, mostly through wonderful dialogue, and she gives more in-depth portrayals of her village’s secondary characters. She creates some of her best comic relief characters.

I’m certain the revisions were crucial. No manuscript is that good without several rewrites. By 1810, Austen had the distance to read her own work with an editorial eye. She also had collected readers’ comments on S&S (novels rarely received reviews), and the criticisms must have suggested such changes as more dialogue and less exposition. One major craft advancement is her excellent handling scenes with multiple people.

Besides, in a letter to her older sister Cassandra, JA’s her first and most trusted reader, JA wrote that she had “lopped and chopped.” P&P is her most tightly written book, though Emma comes close. We know that by the time she wrote the opening chapters of the never completed The Watsons, she was working from outlines and character sketches. She probably was doing that from at least the first draft of P&P.

A letter to Cassandra also tells us that Austen considered Elizabeth Bennet her best protagonist and possibly the best heroine in contemporary novels.

Elizabeth Bennet and Fitzwilliam Darcy remain among the best known characters in English literature. Film adaptations have made them familiar to many people who never read 19th-century novels. Elizabeth is flawed but feisty—and very articulate and outspoken. While she relies too much on first impressions, she learns to revise her hasty judgments, as in accepting that Charlotte is quite content in marrying a boring man (partly because she finds ways to avoid his company) and that Mr. Bennet hasn’t been a good parent. I suspect Elisabeth is the woman Austen would like to have been.

Elizabeth’s quieter, prettier, older sister Jane strikes me as likely to be the closest to Cassandra of any of the major secondary characters. Jane Bennet expects the best from people, but she senses wickedness in the charming and glib Wickham, a classic con man, before others do. He’s one of the few characters with no redeeming virtues.

Darcy is Austen’s most popular male character. I find his treatment of Elizabeth goes beyond pride to an unaccountable social awkwardness. But as Elizabeth said, he looked more appealing once she’d seen Pemberley, his prosperous estate. The remark is both a joke (wealth makes men more attractive) and a truth in that seeing how much his servants respect and like him gives her new respect for him.

The major comic relief characters are some of Austen’s most memorable, partly because they’re really funny and partly because they offer more than humor. The pompous, snobby Lady Catherine runs her estate herself and speaks on the importance of education and the unfairness of the entailment system. The obsequious Mr. Collins, her curate, stands to inherit when Mr. Bennet dies. Mr. Collins comes to the Bennets looking for a wife with the kind-hearted view that since he’s the heir, he should help them out by marrying one of the daughters.

For me and a lot of other writers, P&P is one of the few books worth reading multiple times. JA’s distinctive voice rings strong, and her wit and insight in portraying recognizable people delights again and again.

Northanger Abbey

The book Austen wrote at 23 harks back to her teenage work, written for laughs. Northanger Abbey is a farce, a send-off of the formulaic Gothics popular then. Yet it also has some scenes as good as anything in Pride and Prejudice.

Northanger Abbey has an odd history. She wrote it as Susan in 1798-99, revised it in 1802, and sold it in 1803. The publisher held it, and she finally took it back in the spring of 1816. Somewhere along the way it became Miss Catherine. Her brother changed the title to Northanger Abbey for publication after her death in 1817.

I’ve read that she revised it and that she didn’t revise it in 1816. By then she was not feeling well and was working on other books. Judging from the writing and the content, my guess is that she polished the scenes in Bath, the best part of the book, and barely touched the later portion at Northanger Abbey. It has less humor, for one thing. Certainly she failed to develop Eleanor’s character and to foreshadow her marriage, and that’s not typical Austen. Also she addresses the reader more in this book than in her others.

Her protagonist is Catherine Morland, a naïve but intelligent curate’s daughter in rural England. She reads and takes seriously Gothic novels. She’s 17, which Austen apparently sees as the age when young women are most likely to do stupid things. When the book begins, Catherine has no street smarts and is a terrible judge of people. When the book ends, she’s learned a lot but still doesn’t have the savvy or sophistication of the other protagonists.

Austen begins by telling the reader what Catherine isn’t in terms of the conventions of Gothic novels. The description of Catherine as a child reminded me of something I’d read about Jane as a child. Little Catherine was plain and liked boys’ play, including rolling down hills. Until 10 she was noisy and wild and dirty but kind. At 15 she was much improved—“almost pretty.”

Her wealthy neighbors, the Allens, invite her to go with them to Bath for six weeks, probably because Mrs. Allen doesn’t know anyone and wants someone to go with her to the shops and to the gatherings at the Pump Room. Mrs. Allen, the comic relief character, sees everything in terms of fashion. Catherine asks her if it’s proper to go driving with a man, and Mrs. Allen worries about the wind messing up the girl’s dress.

At the Pump Room, described in considerable detail, they meet Mrs. Allen’s old school friend and her daughters. Both women talk, neither listens. Isabella, the oldest and prettiest daughter, latches onto Catherine as her noncompetitive wing woman in an ongoing hunt for a man with money. Catherine is so unworldly she protests when Isabella flatters her and welcome the manipulative Isabella’s false friendship.

Catherine dances with a young curate named Henry Tillney. He teases her because she’s so naïve and so involved in Gothic novels but recognizes that she’s unusually kind. He’s a bit of an intellectual snob and likes that she listens to what he says and laughs at his jokes. He’s nothing like the distant Darcy.

Isabella succeeds in winning the love of Catherine’s brother, James, an Oxford student who seems more affluent than he is. JA spends few words on James.

Isabella’s brother, John, courts Catherine because he thinks she’ll inherit money from the childless Allens. John is a buffoon and a braggart, which Catherine recognizes when she sees his horse goes half as fast as he claims. She tries to avoid him and spend time with Henry and his shy sister. She also meets their dictatorial, money-hungry father, who mistakenly thinks she will be wealthy and invites her to visit Northanger Abbey. Meanwhile Isabella flirts with the handsome older son, Captain Tillney, the book’s bad guy.

One of the things that’s different about the protagonist of Northanger Abbey is that she doesn’t have another woman to guide her or for her to guide. She’s out there on her own and has to find her own way.

Mansfield Park

Coping with deaths and other family problems interfered with Austen’s writing for several years. She planned and wrote a few chapters of The Watsons in 1804-1805, dropped it, and did little but revise her first two books until 1810 when she sold S&S.

In February 1811 she began work on Mansfield Park, which she finished in May 1814. I think she moved a little too quickly on publishing this one, that it could have used a little lopping. It has a darker tone than any of her books. I suspect she didn’t enjoy writing it as much as she did the first three. She’d called Pride and Prejudice “light and sparkly.” Perhaps she felt she needed to write a more serious book.

The cast of characters suggests Austen had lost some of her optimism about people. The major comic relief character, for example, is downright cruel. A lot of the secondary characters behave not just thoughtlessly and selfishly but destructively.

The protagonist differs in that she’s intimidated by everyone around her. She’s so physically weak she can’t go on long walks (important in JA’s fiction and her life), does not function as part of a family, and for an Austen protagonist, is inarticulate. She resembles the Fanny in Lady Susan, JA’s teenage epistolary manuscript. That Fanny is roguish Lady Susan’s mousy, put-upon daughter. When she finally triumphs, we’re not sure whether it’s mostly luck or a well-developed survival instinct.

Fanny Price comes from more modest circumstances than other protagonists. She’s the daughter of a drunken sailor and a woman who married beneath her. Her wealthy, reserved uncle and lazy, once-beautiful aunt take her in at age 10 at the urging of another aunt, Mrs. Norris. This nasty woman apparently wants someone around who’s lower on the totem pole than she is.

Taken from a large, noisy family and brought into the mansion at Mansfield Park, Fanny is scared, cowed, and lonely. She tries to make herself useful and invisible, and succeeds in both. Mrs. Norris and the two female cousins mistreat her, mostly with verbal abuse, but she gradually becomes indispensable, much like a servant, to her lazy aunt. Only cousin Edmund, who will become a curate, sees the child’s misery and is good to her.

So Fanny becomes a modest, mousy, moralistic, passive, always proper teenager. No one ever thinks about including her in balls, and she’s doesn’t object, partly because she’s not sure she’s strong enough to dance and partly because she views herself much as they do.

On the plus side, she’s extremely observant and skilled at reading character, traits the powerless develop in self-defense. As the self-absorbed slightly older female cousins make a mess of their lives and leave the home, Fanny receives more attention from her uncle and aunt and gains some confidence. To her and everyone else’s surprise, she becomes pretty and is a big hit at a ball. (Where did she learn to dance?)

Naturally Fanny secretly loves her good cousin, Edmund. He’s quite fond of her in a brotherly sort of way. He’s in love with the most interesting woman in the book, the wealthy, beautiful, charming, talented Mary Crawford. She’s taking a break from her usually active social life in the cities and staying with her amiable half-sister, the local curate’s wife. Mary initially likes the older brother, largely because he’s the one who will inherit Mansfield Park, but she comes to love Edmund—conditionally. He either has to inherit or take up a profession that pays well.

JA develops Mary more than most antagonists. She is a multidimensional character. For one thing, she sympathizes with Fanny’s position, treats her well, and teaches her little things that contribute to her growing self-confidence.

The most interesting male character is Mary’s brother, Henry Crawford. He’s wealthy, handsome, charming—a great catch whom the two female cousins pursue. Fanny sees how immoral he is and doesn’t like him. Her disdain challenges the Lothario, and he tells Mary he will make Fanny love him. His sister discourages him from hurting Fanny, but he pursues her and falls so in love he proposes.

To his and the family’s disbelief, she turns him down and resists all pressure to change her mind. Henry appears to have reformed because of his love for her, and even persists after he sees her unappealing lower-class family while she’s visiting them in Portsmouth. She begins to regard him more highly, and I was rooting for this guy—a lot more fun than Edmund. But Harry returns to his immoral ways and runs off with Fanny’s married cousin.

Emma

Austen began her fifth book, Emma, in January 1814, not long after she’d submitted Mansfield Park to her publisher. But Emma has a much lighter mood and a much less villainous cast of characters. As in Northanger Abbey and P&P, Austen was having fun.

From what she told her family, she knew that many readers wouldn’t like Emma as much as her other main characters, but she did. When I read the book years ago, I became annoyed with Emma, but I enjoyed the book far more on this rereading. It’s really well done, second only to P&P in integrating plot and character.

Emma Woodhouse is the most privileged, self-confident, and mistake-prone of JA’s protagonists. She also dominates the book more than other main characters.

The book’s first sentence tells us Emma is “handsome, clever, and rich, with a comfortable home and happy disposition.” She’s 20, which Austen regards as maturity. Her mother is dead and her older sister married, so she manages her father’s household. She’s the village’s Queen Bee with complete confidence in her abilities as a matchmaker and in overseeing the social goings-on in Highbury. The entire book, by the way, is set there. All of the other books have more than one setting. Emma’s arrogant and snobbish and impulsive and thinks her judgment better than anyone else’s. She lacks the self-doubts of all the other protagonists.

Another major difference: She’s happy with her life as a wealthy single woman and has no intention of marrying.

Two things make her a sympathetic character: She’s very good to her difficult father and she’s intends to help people even as she’s messing with their lives. Much of the humor comes out of those two factors.

Mr. Woodhouse is the major comic relief character, a role usually given to a woman. He’s frail and rigid in his ways. A lot of the humor comes from his hypochondria and his concern for his diet and for cold drafts, etc. He warns others about his health concerns, and Emma tries to protect his guests from such things as eating nothing but gruel in the evening. He’s funny, but he’d be hard to live with so Emma’s patience speaks very well for her.

The leading man, George Knightley, is a wealthy neighbor, Emma’s brother-in-law’s brother, and a longtime trusted friend and advisor. He’s about 35, an age Austen favors for men, and acts like an uncle. He’s fond of Emma and feels it his duty to point out her flaws as her father and no one else does. He pretty much expresses Austen’s and the readers’ judgments of Emma’s follies. He’s not particularly exciting, but he’s a good man who values and cares for people regardless of class. And he has no interest in being a curate.

In fact, the curate in this book, Mr. Elton, turns out to be a bit of a jerk. His bride is even worse.

The other major male character is Frank Churchill, the handsome, charming, well-educated young man who has been made a rich relative’s heir. He flirts with Emma and is obviously not as good as he seems, but he’s not a villain like Wickham or a cad like Henry Crawford. Instead he’s covering up his secret engagement to Jane Fairfax, a poor but beautiful, accomplished, and reserved young woman whom Emma sees as a threat to her role as Queen Bee. Unlike Mary Crawford, Jane turns out to be quite principled.

In this book, Austen gives us subtle clues to things Emma’s missing, such as Churchill going all the way to London for a haircut—a cause of great comment in the village—and an anonymous person giving Jane Fairfax a piano a few days later.

We see great changes in the protagonist, much like Catherine in Northanger Abbey.

Persuasion

Austen’s last novel was Persuasion. She began it in August 1815 and had it ready except for a final polish a year later. By then she wasn’t very well, and she never got back to it. Despite such shortcomings as overusing the name Charles and a long chapter revealing the villainy of the protagonist’s suitor being too much of an info dump, it’s a very good book.

Persuasion is shorter than the others, focusing more sharply on the main story. Some believe she intended to write another section. I doubt that for two reasons: She’s concluded the main story, and she wrote twelve chapters of a new book before becoming too ill to work.

The main characters, Anne Elliot and Captain Wentworth, and several of the secondary characters are portrayed with great subtlety, sympathy, and softness. Austen populated Mansfield Park with many dislikable characters. She populated Persuasion with people you’d like to know, notably the older married couples. They don’t fare so well in other books.

I noticed an oddity in her comic relief characters, something she might have tempered in a final pass. The one-note portrayal of vain, arrogant, extravagant Sir Walter, Anne’s father, is so over the top that he’s a caricature. His oldest daughter, Elizabeth, is much the same. His youngest daughter, Mary Musgrove, is no more likable but is much more realistic and much more developed. The fact she’s the baby of the family may be relevant to her being such a spoiled brat and so hungry for attention.

Anne, 27 or 28, is Austen’s oldest and most mature character. At the cut-off age for marriage, she’s the most fully formed personality. Humble and reserved, clever and practical, she’s dismissed by all her family members but valued and liked by others. Again and again, she tales sp;ace in being useful, as when she plays the piano for hours while others dance even though she loves to dance. She had that in common with her creator.

Austen told her niece Fanny, “You may perhaps like the heroine, as she is almost too good for me.”

That goodness, her overdeveloped sense of duty and honor, led her to make a huge mistake. She allowed her mentor to persuade her to reject the proposal of the penniless young naval officer whom she loved deeply. Her father despised Frederick Wentworth because of his lack of wealth and status. When the book opens, Anne has been suffering for letting others sway for eight years. She’s “lost her bloom.”

When newly well-to-do Captain Wentworth returns, Anne hears from obtuse sister Mary that he’s said Anne has changed so much he hardly knew her. The rest of the book, of course, shows them finding their way back together.

Austen had brothers in the navy, and in this book she has four naval officers who are portrayed quite favorably. Wentworth is a bit too good to be true, but that fits with the portrayal of Anne.

Austen’s maturity as a woman and her mastery of craft come out in Persuasion. The interplay of six characters during their long walk and the drama of careless Louisa’s fall show considerable insight and technical skill.

So what did I learn during my mental vacation? Before rereading the books in sequence over about three months, I assumed Jane Austen developed her characters directly from people she knew even though her relatives claimed that only two or three of her characters were based on real people. Now I believe them. I think she was an extremely astute observer and eavesdropper (most writers are), but part of the fun for her as a writer was to create her own distinctive villages.

She drew on her own experiences but didn’t portray herself in any of her protagonists. No one person could have been Catherine in Northanger Abbey, Emma, and Elizabeth Bennet, her favorite. That doesn’t mean bits of her weren’t in all of them.

Jane Austen gave us some of the most memorable protagonists and antagonists in literature, and they’re people as recognizable today as they were 200 years ago. That’s why we’re still reading her books.

I enjoyed spending time exploring Jane Austen’s villages.

Making the Most of Mistakes

Kristina Stanley invited me to share a list of 10 common mistakes mystery writers make on her Mystery Monday blog at .https://kristinastanley.com/2017/03/27/mystery-mondays-author-carolyn-mulford-on-10-common-mistakes/#comment-18812.

For years I’ve been talking about improving both nonfiction and fiction writing by identifying and correcting typical errors. By knowing what those are, you can catch them as you write the first draft or read the completed one.

What I haven’t emphasized is what you gain by making certain mistakes—in the first draft. For example, writers often delay action and bore readers with info dumps. As an editor, these drive me nuts. As a writer, I recognize the value of writing long, of putting everything in the first draft. In the second draft, we must delete, choose telling details, and move content to the most effective spot.

Writers need to know much more than their readers in order to select what to tell them. For example, we must research details about how a poison works or analyze the traumatic effect of a pre-book incident or trace a realistic provenance of a stolen painting. Once we know such things, we find it hard to resist an info dump, but the reader doesn’t need or want all that information.

The thing is, including all our research and conceptualization in the first draft puts it right where we can find it and gives us an opportunity to select the right nuggets in the next, or a later, draft.

Info dumps can pop up anywhere, but they’re particularly deadly in the opening when lengthy backstory, description, or academic discussions delay action. Insert your little gems with adjectives, phrases, and sentences, not paragraphs, pages, and chapters.

Bad mistakes, if recognized, can lead to better writing. After all, we usually learn more from our failures than our successes.

—Carolyn Mulford

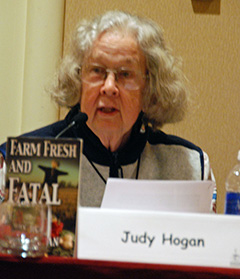

Judy Hogan Makes Community a Character

A mystery series must have a strong protagonist. For Judy Hogan’s Penny Weaver series, that’s a middle-aged poet/teacher and activist who marries a Welsh police officer and moves back and forth between a Welsh village and rural North Carolina.

In the latest book, Nuclear Apples?, Penny remains the point-of-view character, but the real protagonist is the diverse community of activists fighting dangerous practices in a local nuclear power plant.

Almost anyone who has taught has seen a class take on a collective personality without submerging the individuals. The author shows this same collective personality in her activists, who include a toddler eager to break all his parent’s rules on healthy eating, teenagers finding love in an apple orchard, and an ingenious deputy determined to protect the activists during demonstrations.

The collective and individual personalities stand out in scenes in which they gather to plan—and to eat. Writing a scene that the reader follows without pause is easy when you have only two or three people. Portraying a group of people sharing a meal takes considerable skill. Picture those grand Downton Abbey meals where the camera shows a wide shot and then focuses on speakers in turn in a seamless scene. The author accomplishes the same feat without visual aids.

She gives a cast list at the beginning, and I groaned in anticipation of having to refer back to it to keep so many people straight. To my surprise, I didn’t. Several times I had to stop to think which wife went with which husband, and I lost track of who was older or younger and who was black or white. But that’s part of the point. It doesn’t matter.

The most memorable interactions are those between family members caught up in personal crises as they link lives to fight for the community. Penny stays in the middle of it all.

Nuclear Apples? is available in Kindle and print editions.

—Carolyn Mulford

Guest Blog: Judy Hogan on Trusting the Muse in Writing Mysteries

Poet, novelist, memoirist, writing teacher, and activist, Judy Hogan draws on life experience for everything she writes. To see the range of her writing and sign up for a chance to enter a giveaway of her latest mystery, Haw: The Second Penny Weaver Mystery, visit her page on GoodReads.com. The giveaway ends April 26.

Poet, novelist, memoirist, writing teacher, and activist, Judy Hogan draws on life experience for everything she writes. To see the range of her writing and sign up for a chance to enter a giveaway of her latest mystery, Haw: The Second Penny Weaver Mystery, visit her page on GoodReads.com. The giveaway ends April 26.

My main guide to all my creative writing is from Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own:

“As long as you write what you wish to write, that is all that matters, and whether it matters for ages or only for hours, nobody can say. But to sacrifice a hair of the head of your vision, a shade of its color, in deference to some Headmaster with a silver pot in his hand or to some professor with a measuring-rod up his sleeve, is the most abject treachery, and the sacrifice of wealth and chastity which used to be said to be the greatest of human disasters, a mere flea bite in comparison.” (P. 110)

That advice has stood me in good stead since my twenties. I find it elsewhere, too. Elizabeth George, in her Write Away, says much the same thing. Louise Penny tried for five years to write a novel, and then decided to write the kind of book she loved, the traditional mystery. And she created a world she wanted to live in. She had trouble getting published until she was short-listed for the British Crime Writers best first mystery novel. She now hits The New York Times Best Seller lists.

I write what I wish to write, always have. I began reading mysteries in 1980, at age forty-three. Mysteries then seemed to be at the opposite pole from writing poetry. They do take different approaches, but in both cases I trust the Muse, or the Deep Unconscious, once I’ve worked out my characters and scenes, to give me first lines.

Quite a few well-known authors say they don’t plan, but I like George’s approach to fleshing out the characters first, learning their world, then drafting my way through all the scenes–in rough fashion, i.e., who’s in them, what the conflict is, what they are doing, sometimes a bit of dialogue. This is the hardest part, but I find, as I’m developing the characters and scenes that, if I ask myself questions, I get answers. That might come from years of writing poetry and diary, and going deep into my feelings. Then, as I write, I learn what I know about people that I didn’t know I knew.

All my life experiences go into my writing. In one way everything I write is autobiographical, though in fiction I take off from what I experienced into what I can imagine might have happened had the conflicts gotten even worse.

I also like taking up community issues which disturb me and which I’ve worked on myself. When you’ve sold at a farmer’s market, you learn about the behind-the-scenes conflicts, or in local politics, how the good guys can get power-hungry, and also how reluctant people are to change their views, especially about politics and religion.

I like to see stereotypes drop to the ground. Mine have over the years as I’ve come to know how much variety there is in people, and I try to get that into my characters. I like to read authors who explore people’s attitudes and behavior, and give us real people. What does motivate people who abuse power and try to control others? What causes some to find courage or persist when their cause seems hopeless?

I have had a few students in my novel classes writing mysteries, and I tell them they have to share on their page their characters’ inner feelings, the knowledge of which comes from knowing their own. The more you have access to and acceptance of your own feelings, the more you can create characters people care about. Then your readers keep reading, because you’ve generated suspense, i.e., they have to know what is going to happen.

I find you need to have interruptions every so often, to keep the pace going. To me, as a reader, good pacing doesn’t mean rushing and interrupting the flow with new events all the time, but it does mean that things happen to cause the plot to move in a new way before the reader gets bored. It should feel seamless, though a surprise, and still, not entirely unexpected. Some new difficulty for the sleuth might in the end help the plot toward resolution.

Elizabeth George is so conscious of everything she does, but even she says, “Trust your body,” which for me is trusting the Muse, trusting those impulses that come out of the blue. Maybe sometimes you start to feel bored and ask yourself what interruption can I have now, to jog the plot along better, and you get an answer.

You can learn these things and so many others by reading gifted writers of the past and present. Sometimes you can’t begin to imagine where you learned what to do with the plot or the characters in conflict. Some comes from stored experience and some from wide reading of the best possible models. With mysteries, go back to the Golden Age, Josephine Tey, Dorothy Sayers, Agatha Christie, Michael Innes, Ngaio Marsh, But also read Trollope and Jane Austen, Henry Fielding and Lawrence Sterne. You’ll write better when you’ve read those classics. I’ve seen it happen, and it amuses me to learn that George reads a little Jane Austen or equivalent before she starts to write.

Mainly, make yourself happy. Enjoy it. Persist, learn, read, and never give up.

Mainly, make yourself happy. Enjoy it. Persist, learn, read, and never give up.

Judy Hogan

Coming May 1, 2016: Haw: The Second Penny Weaver Mystery, Hoganvillaea Books, 190 pp. Paperback: $15.00, ISBN-13: 978-1518818141; e-book: $2.99.

Book description: Penny Weaver, living in a shared house to save money, finds her unsavory, sex-obsessed landlord dead the day after Christmas. An unusual snowstorm, a housemate undeterred by detective orders from moving his numerous possessions, and certified and uncertified maniac suspects (including the neighbors and both the landlord’s wives) make it difficult for Penny and her Welsh lover to find love-making time, much less solve the mystery. Despite the sheriff’s detectives keeping Penny in the dark and arresting two innocent people, she persists in collecting key information in order to stop the killer.

Judy Hogan brought Hyperion Poetry Journal (1970-81) to North Carolina in 1971, and in 1976 she founded Carolina Wren Press. She has been active in the Triangle area since the 1970s as a reviewer, publisher, teacher, and writing consultant. In 1984 she helped found the N.C. Writers’ Network and served as the president until 1987.

Her first published mystery novel, Killer Frost, came out from Mainly Murder Press in 2012, followed by Farm Fresh and Fatal in 2013. Under her own imprint Hoganvillaea Books, she published The Sands of Gower: The First Penny Weaver Mystery in December 2015, and she will bring out Haw: The Second Penny Weaver Mystery, May 1, 2016. She has published six volumes of poetry with small presses and two prose works. She taught Freshman English 2004-2007 at St. Augustine’s College in Raleigh. She does freelance editing for creative writers and offers workshops.

Judy lives and farms in Moncure, N.C., near Jordan Lake. Her blog, postmenopausalzest.blogspot.com, often has reviews and interviews featuring contemporary mystery writers. Her website is judyhogan.home.mindspring.com.