A North Carolina author, teacher, and activist, Judy Hogan has written everything from mysteries to poetry to memoir. (For more about her and her work, visit http://judyhogan.home.mindspring.com.) Even so, editing and annotating her grandparents’ diary evoked emotions her other books didn’t. She tells us why she worked so hard to pull together information on their life in China.

Judy Hogan

Probably the most important event of my life was going to Russia in 1990 as part of a Sister Cities of Durham Russia writer exchange program, and all the experiences that followed from it, with many visits and mutual publishing projects. The second most important event happened in April when my book of and about my grandmother’s diary was published. Here my learning experience was related to China, where my mother was born and her parents were missionaries 100 years ago.

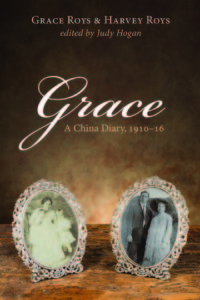

Grace: A China Diary, 1910-16 arrived in my post office Saturday, April 15. We’re a village, and we chat in the post office. I was chatting with a friend I rarely see, and our postmaster, Robin, handed me a priority envelope from my publisher, Wipf and Stock of Eugene, Oregon. I tore it open, and there was a shrink-wrapped package, with a sheet of paper over the cover. “I need scissors,” I said.

Robin provided them, and I got the two paperback books free of the plastic. There it was. I let Robin hold one (she had already said she’d buy it), and a man named Mr. Moon asked if it had pictures in it. I showed him the pictures near the front and said, “That was in China in the early 1900s.” He said he wanted a book, too.

I’d been able to publish 14 books before Grace arrived. Why was it such a big deal? Here’s part of the answer, from the first chapter of Grace.

Finding Grace: By age six one of the most important people in my life was Grace, my maternal grandmother, who, with her husband Harvey Roys, had been a missionary in China. Closely tied to Grace was another Grace, her daughter, born September 1915, who died at age eight in 1924 from heart complications following scarlet fever. Early in 1944 my mother moved my sister and me from Cameron, a small town in West Virginia, where my father, William Robert Stevenson, had been the minister of the Presbyterian Church, and where I had felt loved and protected on all sides, to Norman, Oklahoma. My father had volunteered to go into the Navy as a chaplain and was stationed in McAlister, not far from Norman, where my grandfather and grandmother Roys lived. Grandpa taught physics at the University of Oklahoma there.

Finding Grace: By age six one of the most important people in my life was Grace, my maternal grandmother, who, with her husband Harvey Roys, had been a missionary in China. Closely tied to Grace was another Grace, her daughter, born September 1915, who died at age eight in 1924 from heart complications following scarlet fever. Early in 1944 my mother moved my sister and me from Cameron, a small town in West Virginia, where my father, William Robert Stevenson, had been the minister of the Presbyterian Church, and where I had felt loved and protected on all sides, to Norman, Oklahoma. My father had volunteered to go into the Navy as a chaplain and was stationed in McAlister, not far from Norman, where my grandfather and grandmother Roys lived. Grandpa taught physics at the University of Oklahoma there.

Living with my grandparents at that time was also their younger son, Harvey, who was in medical school. Mother had taken a job with the YWCA on the O.U. campus. There were two naval bases in Norman, and housing was hard to find, so we lived three months in a small house with my grandparents and my uncle.

For the first time in my life I wasn’t happy. My school teacher was harsh, threatening us all with being sent to the principal if we misbehaved. She was said to have a rubber hose with which she beat children. I was missing my father. Uncle Harvey, whom I at first had admired, had little sympathy for a six-year-old. My grandfather was impatient, too, when I complained about the long walk to school—about a mile. He said he’d walked farther than that when a child. Grandmother Grace startled and scared me when I encountered her as she was waking from a nap in the basement room. She told me she had dreamed she had gone to heaven to be with Gracie. She seemed sorry to have awakened.

Mother wasn’t happy either. Her new-doctor brother Harvey told her she should have the lump in her breast removed immediately. Then he heard me complaining about my long school walks and how my legs ached, and he urged Mother to take me to a doctor, as I might have rheumatic fever. The diagnosis was confirmed by the local doctor. Somehow during this time, I identified myself with my mother’s little sister, Gracie. The family myth about Gracie was that she had been angelic. By the time she died, she had found her lord and savior. Gracie went straight to heaven. No one else could compete with her goodness, especially after she died.

By the time Mother found us a very small house to rent in May, conveniently across the street from a different and kinder elementary school, I had been diagnosed with rheumatic fever, and bed rest was ordered. I lived in bed for a year. At first Mother arranged babysitters for me and my little sister, Margaret Elaine, so she could keep her new job, but she quit before long and stayed home with us. Gasoline was rationed, but every now and then Grace and Harvey drove across town to visit us. Grandmother gave us rabbits one Easter. For many mornings after that Mother had to chase them down, as they got out and into the neighbors’ gardens. Finally one died, and she encouraged a little boy who was visiting me to take the other one home. I learned much later she was afraid to get rid of the rabbits openly because they had been her mother’s gift to us. I didn’t know then that Grace had bi-polar disease. This might explain why Mother didn’t want to upset her mother.

***

It’s hard to go back to your early life and take on the ghosts that are still there, and try to put them to rest. Mother was my main source of information about Grace, her mother, who had been unreliable for her, beginning at age 12, when she had to be hospitalized. She described her mother as “brilliant, high-strung, highly sexed, artistic, and crazy,” and without her ever saying this aloud, my sister and I felt like we were being watched for the craziness to come out. We were talented, she in music, I in writing, and we had a normal interest in sexuality. We were smart, but probably not brilliant. I had a line in my head which I sometimes quoted in newspaper interviews: “If I didn’t write, I’d go crazy.” I eventually learned in therapy that I had unconsciously identified both with Grace and her daughter, Gracie.

Mother gave me a lot of family papers, including the diary that Grace and her husband Harvey had kept in the early years of their marriage, 1910-16, and in 2004 I decided to annotate it and try to publish it. I had friends make suggestions, and I researched China, even though I had taken a dislike to China in early childhood when Mother explained that the Chinese devalued girls and sometimes put them to death. Research isn’t my favorite writer thing to do. I like to write from my own experiences and imagination, but something urged me to understand Grace, even if it meant dealing with China. I had helpers all along the way, and gradually got past my negative feelings about China and came to love Grace.

Only toward the end did I stumble on the fact that Grace’s mental illness probably got worse because her first 32 years had been spent in China, with those wise, loving servants, and in the missionary community which was also loving and supportive, and in Oklahoma where they ended up, she had one college girl living in to help her, and she had three school-age children to cope with, and no supportive community. She spent most of the rest of her life in Oklahoma’s Central State Mental Hospital.

I think I was wanting to redeem her, be the artist she had failed to be. It hit me a few days ago that she was Henry James’s “failed artist,” the perfect character for a novel. The book is all true, but it has the story of Grace, mostly in her own words in the diary. In those years she was happy, loved her babies, was an important member of the Nanking missionary society, played organ and piano, led children in Christmas music, went on little jaunts with Harvey, as well as hunting and chasing wild pigs on horseback. So Grace is out there now, and people are buying it, more than I expected, and its being out there comforts me.

***

Here’s the key info: Grace Woodbridge Roys suffered from bi-polar disease before it was well understood. Her daughter feared that her children would also suffer mental illness. This annotation of Grace’s diary opens the early 1900s missionary world in China and the personality of Grace to the reader. In December 1910 Grace married Harvey Curtis Roys, who was teaching physics at Kiang Nan government school in Nanking, under the sponsorship of the YMCA. Grace had had a mental breakdown weeks earlier when her missionary father forbade the marriage.

The diary records their early married life, the births of their first two children, their social life with other missionaries in China, many of whom made major contributions to Nanking life and education: medical doctors and nurses; theology professors; agricultural innovators; founders of universities, hospitals, nursing schools, and schools for young Chinese women and men. Included is their experience evacuating during the Sun Yat-sen Revolution of 1911. Well-known missionaries of that time came to tea and taught at the Hillcrest School the mothers began for foreign children. The Nanyang Exposition took place in 1910, too, as China was in the throes of entering the modern era, with trains, electricity, telegraph, and a new interest in democracy.

***

Comments from Experts: “This thoroughly annotated five-year diary, including contemporary accounts of the retreat colony Kuling and schools in Nanking, provides rich and illuminating primary documentation toward understanding the daily personal, family, social and professional lives of American educators and missionaries in early 20th century China, the native culture in which they devoted themselves, and their influence on subsequent generations. A graceful window on the lives of Westerners and Chinese alike.” J. Samuel Hammond, Duke University.

“Grace, a rich portrait of missionary life in early 20th century China, is told through diary entries, photos, narratives, and an epilogue by Judy Hogan, editor and annotator of her grandmother’s diary. Most poignant for me, as a former missionary child, is Hogan’s appreciation of Grace’s difficult transition from the China where she spent her first 32 years to the United States where her mental illness took flight.”–Nancy Henderson-James, author of Home Abroad: An American Girl in Africa

Grace: A China Diary, 1910-16, edited and annotated by Judy Hogan. Authors: Grace and Harvey Roys. Wipf and Stock, Eugene, Oregon. ISBN: 978-1-5326-0939-8. Paperback: $26; Kindle, $9.99. Independent bookstores may order from Ingram or www.wipfandstock.com. For signed books, send order ($30 including tax and postage) to Judy Hogan, PO Box 253, Moncure, NC 27559.

Finding Grace: By age six one of the most important people in my life was Grace, my maternal grandmother, who, with her husband Harvey Roys, had been a missionary in China. Closely tied to Grace was another Grace, her daughter, born September 1915, who died at age eight in 1924 from heart complications following scarlet fever. Early in 1944 my mother moved my sister and me from Cameron, a small town in West Virginia, where my father, William Robert Stevenson, had been the minister of the Presbyterian Church, and where I had felt loved and protected on all sides, to Norman, Oklahoma. My father had volunteered to go into the Navy as a chaplain and was stationed in McAlister, not far from Norman, where my grandfather and grandmother Roys lived. Grandpa taught physics at the University of Oklahoma there.

Finding Grace: By age six one of the most important people in my life was Grace, my maternal grandmother, who, with her husband Harvey Roys, had been a missionary in China. Closely tied to Grace was another Grace, her daughter, born September 1915, who died at age eight in 1924 from heart complications following scarlet fever. Early in 1944 my mother moved my sister and me from Cameron, a small town in West Virginia, where my father, William Robert Stevenson, had been the minister of the Presbyterian Church, and where I had felt loved and protected on all sides, to Norman, Oklahoma. My father had volunteered to go into the Navy as a chaplain and was stationed in McAlister, not far from Norman, where my grandfather and grandmother Roys lived. Grandpa taught physics at the University of Oklahoma there.